Nimitz-class aircraft carriers USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70) and USS Nimitz (CVN-68) transit the Pacific Ocean on Feb. 13, 2022. US Navy Photo

Some Nimitz-class aircraft carriers could remain in the fleet longer than previously anticipated, two Navy officials said on Wednesday.

The service is currently studying extending the service lives of the oldest Nimitz-class aircraft carriers, Jay Stefany, who is currently performing the duties of the assistant secretary of the Navy for research, development and acquisition, told reporters in a phone call Wednesday.

“I don’t know when that’s due to be reported out, but that is part of our [Program Objective Memorandum] 24 efforts that we’re working on now is how that would play out as far as potentially extending at least a couple of the first Nimitzs,” Stefany said of the study.

While the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2023 30-year shipbuilding plan shows the service decommissioning USS Nimitz (CVN-68) in FY 2025 and USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) in FY 2027 – which aligns with the carriers’ 50-year service lives – the Navy still has time to alter that plan if necessary.

“Nimitz was supposed to go into a late Fiscal Year ’23 [availability] where the extension could have been done. Bottom line is we will revisit Nimitz as part of the FY-24 shipbuilding plan,” Vice Adm. Scott Conn, the deputy chief of naval operations for warfighting requirements and capabilities (OPNAV N9), said during the same media call.

Conn described extending the lives of any of the Nimitz-class carriers as “pre-decisional.”

“There are questions based on real-world events – does it make sense? Based on the number of planned carriers we may have in maintenance in certain years, it may make sense and maybe worth the return on investment of getting another year or more from the carriers that we have,” he said.

The Navy has been mulling extensions for the Nimitz-class carriers for the last few years. In September 2020, Program Executive Officer for Carriers Rear Adm. James Downey said Nimitz had more potential beyond its scheduled timeline and that it could be in service from 52 to 55 years.

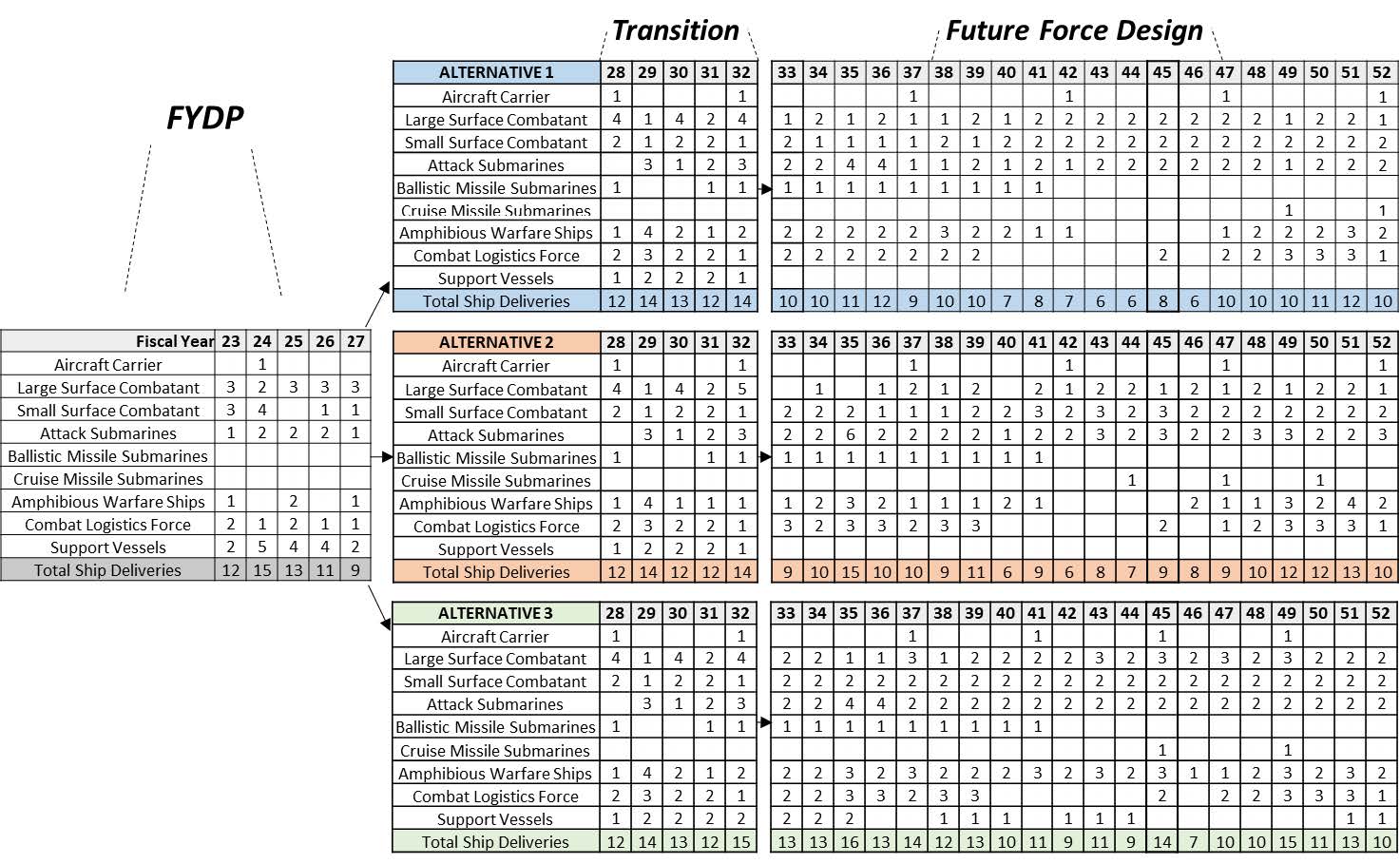

Conn and Stefany spoke about the Navy’s release of its long-range shipbuilding plan, the first one the service has put out in three years. In a departure from previous versions of the document, the Navy put forward three different options for procurement plans.

“Without real budget growth, the two low range options achieve 305-307 manned ships in FY2035, and ultimately 318-322 manned ships in FY2045. The higher range achieves 326 manned ships in the mid-2030s, and ultimately 363 manned ships in FY2045. The above inventory levels are traditional manned battle force ships,” the document reads.

Conn described the three alternatives as providing options to lawmakers.

“This is really options for the Navy. We prefer to do our own business but then in their oversight role they certainly get a vote,” he said of Congress. “And again this is about giving indicators to industry. But this in total is not a requirements document. It doesn’t set requirements. It executes to what the warfighter requirements are.”

The proposal includes a “transition” period for FY 2028 to FY 2032, which Conn and Stefany said is part of the Navy’s push toward a hybrid fleet of both manned and unmanned systems.

“There’s technical uncertainty that we have to drive out, which will then drive to certain solutions – understanding where artificial intelligence is going to be at a point in time, understanding the level of autonomy that we need to do and execute the missions, in terms of where we need to execute them,” Conn said. “We have to technically drive down those risks and when we do, the ranges will get tighter and tighter and closer to a single point solution within 10 years of the budget that you are writing.”

Stefany said the three different alternatives give both lawmakers and industry an idea of what the Navy’s options are for a budget without any growth and where it could go if the service received more funding.

“We wanted to lay out a floor, if you will – the floor being no real growth, inflation. But we also wanted to give Congress and industry a heads up of where we would like to go if there were more resources available to the Department of Navy and what we thought we could actually do at that time, right, within [what] the industrial base can handle,” he said.

The blueprint, which is legally mandated by Congress, includes a range for unmanned systems but does not break the platforms out by potential programs, like the Large Unmanned Surface Vehicle (LUSV) and the Medium Unmanned Surface Vehicle (MUSV).

“In addition, unmanned platforms will achieve 89-149 platforms in FY 2045 without real budget growth. Future force levels will be adjusted as the capabilities of unmanned platforms develop and are integrated into the battle force,” the plan reads.

Both Conn and Stefany said the Navy has more testing and experimentation to do in the next few years, as the service moves from testing unmanned systems to testing manned and unmanned teaming.

“Understanding the software development is critical and you see in the shipbuilding plan as the profiles, you have the [Future Years Defense Program] and then you have this transition phase for five years. That is all about planting the seed corn to make sure we have the software development work done before we get into the force design phase, which is about the hybrid fleet that starts in 2032 and out,” Conn said. “That doesn’t mean we’re going to wait to 2032. As technologies mature, we will put them into the fleet. But that shipbuilding plan gives you a roadmap of the types of things we’re going to do and our priority of effort because what we cannot accept is to have concurrent software development and hardware development at the same time. And we have to get in front of the software.”

Conn described the second procurement option as a more robust pursuit of unmanned systems.

“Alternative two is a little bit more aggressive with unmanned systems than alternative one, but that’s more out there in the end of this decade and into the 2030s. But that is where the difference is because if you look at the numbers, it’s from 318 to 322,” he said. “It’s only four ships difference. But the makeup of that force and the level of autonomy through unmanned systems that is probably the biggest difference.”

Under the third option, Conn said the number of unmanned systems would likely be closed to the higher end of the range provided, or 149.