The HMS Hermes arrived too late to change the course of the First World War. But it arrived just in time to change the course of world history.

One hundred years ago, the W. G. Armstrong-Whitworth shipbuilding company laid down the hull of the world’s first aircraft carrier at Walker, U.K. World War I, which saw the introduction of fighters, bombers, and bomb-dropping airships, was in its final months. The modest Hermes was just 600 feet long and carried just 15 Swordfish torpedo bombers. But the revolutionary idea behind it shaped the next great war and the next century of the world’s navies.

A century later, hundreds of carriers patrol the world’s oceans. These mega-vessels are still considered the pinnacle of sea power, but they are also, in a way, giant floating targets. New anti-carrier weapons threaten their existence—as do the spiraling costs to build them in the first place.

Has the age of aircraft carriers ended? Or has it just begun?

The Carrier Ascends

There’s a reason the first carrier came out of the U.K. While the Royal Navy was convinced this blazing new technology had a big future, the United States Navy resisted the idea of carriers as a decisive weapon at sea.

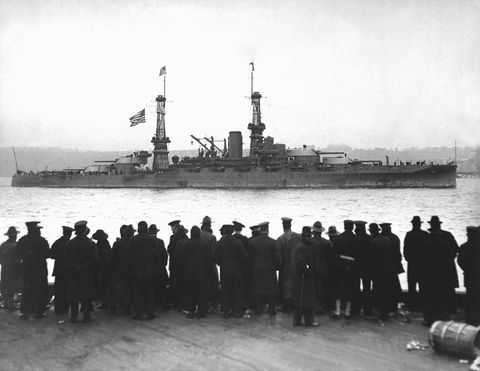

To the American navy, planes based at sea were scouts, the eyes and ears of fleets equipped with battleships and cruisers. Those big ships had dominated the seas with their big guns, which measured up to 18 inches in diameter in the case of Japan’s Yamato class, with ranges of up to 20 nautical miles. A single Iowa-class battleship packed nine 16-inch guns, each hurling 2,700-lb shells. Gunships located the enemy, closed on it, and bombarded it with overwhelming firepower.

Airpower advocate Gen. Billy Mitchell, one of the architects of the U.S. Air Force, turned the tide. He demonstrated in a series of tests in 1921 (including the sinking of the captured German battleship Ostfriesland) that planes could locate and destroy enemy ships. The Navy began to see the possibilities for planes as a separate striking arm, one that could see farther and attack at greater ranges.

The death knell for the battleship age came on the day that will live in infamy. In the years leading up to World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy had gone all-in on the carrier concept. Six aircraft carriers led the strike force that hit the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor with a surprise attack on December 7, 1941. In one day, carriers proved they could do what battleships could not: cripple a fleet hundreds of miles away. The range difference doomed battleships, which went from being the hunters to the hunted. Only one battleship, HMS Vanguard, was commissioned after the end of World War II.

The Carrier Evolves

Aircraft carriers have reigned supreme since 1945, and those in the United States’ fleet have not faced a mortal threat since V-J Day. U.S. Navy carriers have provided crucial air support in the Korean War, Vietnam, Grenada, Desert Storm, the Balkans, Afghanistan, the invasion of Iraq, and the war against the Islamic State. None of America’s adversaries have had the power to even remotely threaten her carriers.

What if the next enemy does? Today, the United States faces two navies with the potential to threaten U.S. aircraft carriers. Russia’s new Yasen-class guided missile submarines, with their ability to launch salvos of Klub anti-ship missiles, along with China’s growing fleet of aircraft carriers, destroyers, submarines, and anti-ship ballistic missiles, represent the greatest threats to American carriers since the end of the Cold War.

To win the future, the designers and builders of carriers must amplify their strengths and come up with clever ways to mitigate their weaknesses.

Carriers can do what no other vessels can. As U.S. Navy admirals are fond of saying, carriers are “4.5 acres of sovereign American territory,” capable of operating from virtually any saltwater location on Earth. The U.S. Navy’s Nimitz and Ford-class carriers can accomplish counter-air (air-to-air), anti-ship, anti-submarine, land attack, reconnaissance, and disaster relief missions—and even potentially lead a nuclear strike. Thanks to mid-air refueling, there are few places carrier-based planes can’t go.

An aircraft carrier is perhaps the most adaptable of any large military technology. Its ability to accommodate any plane is what keeps it at the top of the food chain. If flat-tops could only handle the Hellcat fighters of World War II, they’d be obsolete. Instead they carry an evolving array of aircraft that today includes F/A-18E/F Super Hornets and F-35 Joint Strike Fighters, planes far more capable than the prop-driven fighters of World War II. Unlike most military systems, the aircraft carrier stays relevant by taking on new technologies with ease.

Yet carriers face an increasing number of threats stemming from one big problem: They are huge, hulking targets. They concentrate firepower and capability, but they also concentrate people: each Nimitz-class carrier is home to more than 5,000 sailors and Marines meaning the sinking of a single one could see more Americans killed in action in a single event than were lost on 9/11. These great vessels now face threats from aircraft, anti-ship missiles, submarines, nuclear weapons, and even anti-ship ballistic missiles. Minimally armed, they must rely on their escorts to defend them.

And there is the issue of the ever-escalating cost to produce them. During World War II, the average Essex-class fleet carrier cost somewhere in the vicinity of $75 million, and Hellcat fighter planes cost $50,000 each. Adjusted for inflation to today’s dollars, that’s $1 billion for the ship and $690,000 for the plane. Today, a Ford-class carrier costs $13 billion, and the modern equivalent of the Hellcat, the F-35C Joint Strike Fighter, costs $121 million apiece. This is an unaffordable trajectory, making fewer carriers and planes affordable—and their loss in combat irreplaceable.

The Carrier Continues?

America isn’t the only country still banking on carriers. China has built two aircraft carriers and is building two more. The United Kingdom is building two carriers, Italy has two carriers, France has one, and Russia is struggling hard to keep its lone carrier, Admiral Kuznetsov, in service. Japan, once the owner of the most powerful carrier force in the world, has a fleet of three helicopter-capable carriers and is investigating operating F-35 fighters from the two largest.

As long as air power is viable, aircraft carriers will have a future, but they need a few key moves to remain relevant. One is the adaptation of unmanned aerial vehicles for most air missions. Drones are much cheaper than manned aircraft, and their loss in combat doesn’t result in a captured pilot. The Navy could also invest in smaller, cheaper carriers to bring costs down.

Another way would be to make them hard to kill. Rather than a colossal ship topped by a runway, picture a drone-operating submarine that surfaces only to launch and recover aircraft, which would be much harder to detect during wartime. Spreading air power among smaller submarine carriers networked by secure datalinks could disperse firepower while still concentrating it for key missions.

If the Navy succeeds in countering these problems, carriers could sail on—above or below the waves—for another hundred years. If not, then the nation may be in for a rude shock the next time it goes up against another naval power.