USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70) transits the Pacific Ocean while underway in the U.S. 3rd Fleet area of operations on Aug. 4, 2018. US Navy Photo

This post has been updated to include an addtional statement from the Navy as well as an explanation of how USNI News tabulated its data.

THE PENTAGON – Aircraft carriers – the most visible tools of U.S. military power – are spending more time in maintenance and at home even as the Pentagon has declared it’s entered a new era of competition with China and Russia.

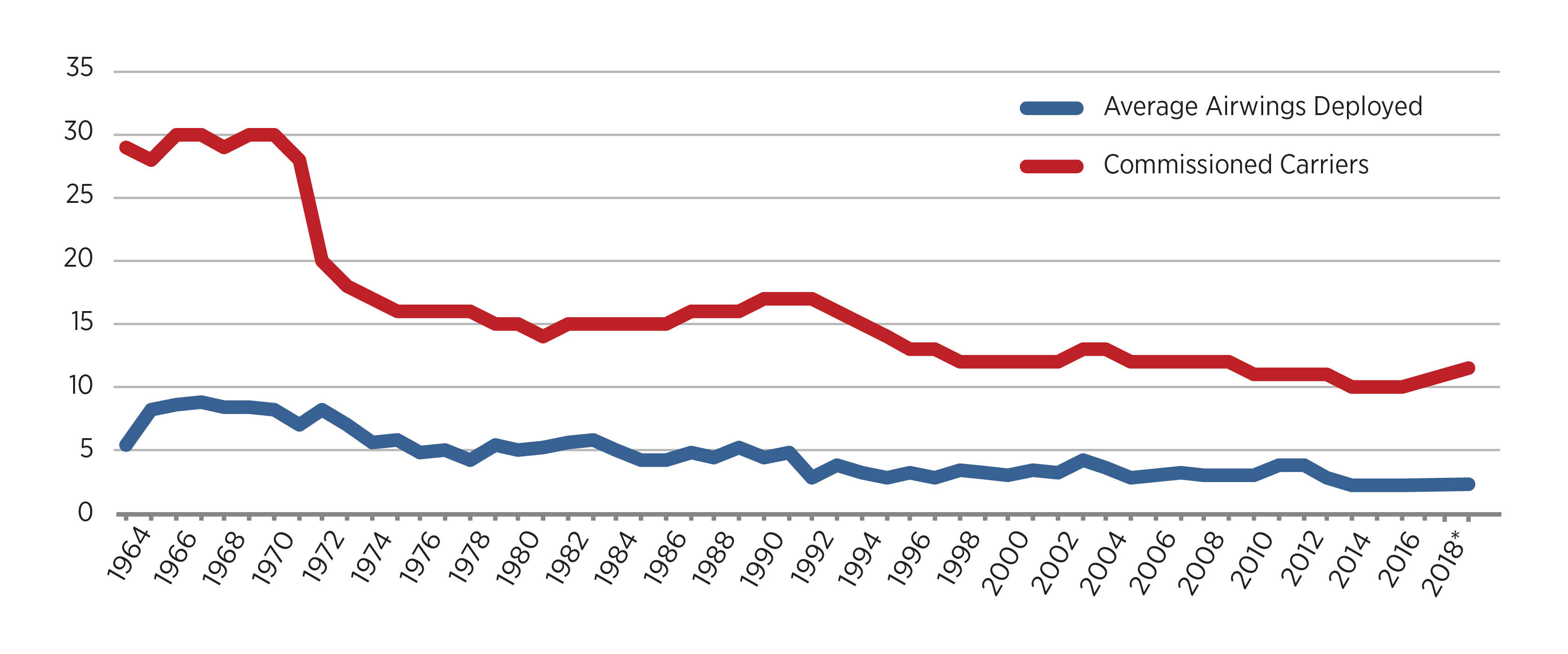

According to a USNI News analysis of more than 50 years of carrier air wing deployments over the last 15 months, the Navy has seen the lowest number of carrier strike groups underway since 1992, the year following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

*Year to date USNI News Graphic

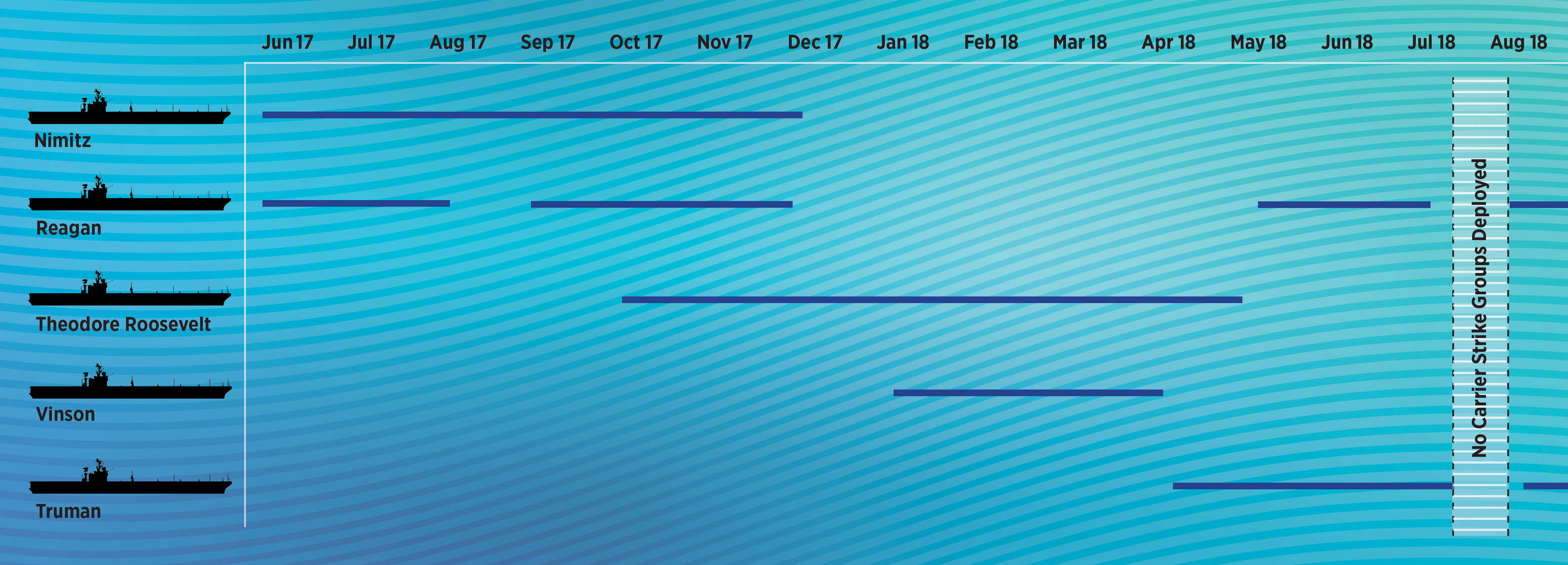

The Navy has deployed about 22 to 25 percent of its carriers since 2013. That total — which excludes training missions and exercises — is down from a 28-percent average for the rest of the era of the global war on terror. In 2018, to date, that number has been down to an average of about 15 percent of the Navy’s carriers committed to operational deployments.

For 22 days this summer, the Navy did not have a full carrier strike group deployed anywhere in the world available for national tasking, the service confirmed to USNI News. That’s the longest gap in the years USNI News studied.

In a late Thursday statement, after publication, the Navy said it was prepared to deploy forces at any time.

“The Navy is the nation’s global maneuver force and has the capability and capacity to respond to worldwide requirements at any time,” Navy spokesperson Capt. Greg Hicks told USNI News.

How We Counted:

In analyzing the deployment numbers of U.S. carrier strike groups, USNI News used a specific methodology that measured operational combat power.

The totals used in this story do not count training exercises, certification cruises or other qualification underways, but rather only include operational carrier deployments focused on national tasking.

For example: For 22 days this summer — under those counting rules — the U.S. did not have a fully certified carrier strike group underway available for national tasking.

During that period USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) was underway certifying its airwing and not available for tasking. Also in that period, USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70) was participating in the Rim of the Pacific Exercise and not in direct control of its escorts. Neither of those underway periods was counted in the USNI News counting of full carrier strike groups capable of national tasking.

According to service leaders, the drop in presence comes as the Navy is struggling to pay off the maintenance tab for the carrier force that the Pentagon ran up during the 17 years of the global war on terror.

*Year to date USNI News Graphic

“After 9/11 – and all those evolutions for the ground team, our focus was supporting the ground fight, which meant we were operating that force a lot, and when you operate the force a lot it eats up a lot of your cash, it eats up a lot of your service life,” Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Bill Moran told USNI News in an interview last week. “The Navy got smaller to help offset the cost of a lot of those things. So, modernization wasn’t coming along at the same pace as it might have, with forces that were faced with the adversary every single day. Our job was to support [ground forces], and we have done it really well. But it’s against a team that’s maybe a minor league team, when it comes to maritime forces, not the major league team that we want to be ready for.”

The Chinese and Russian navies are those major league teams, and both have been expanding their maritime forces while the U.S. Navy largely marked time in a supporting role.

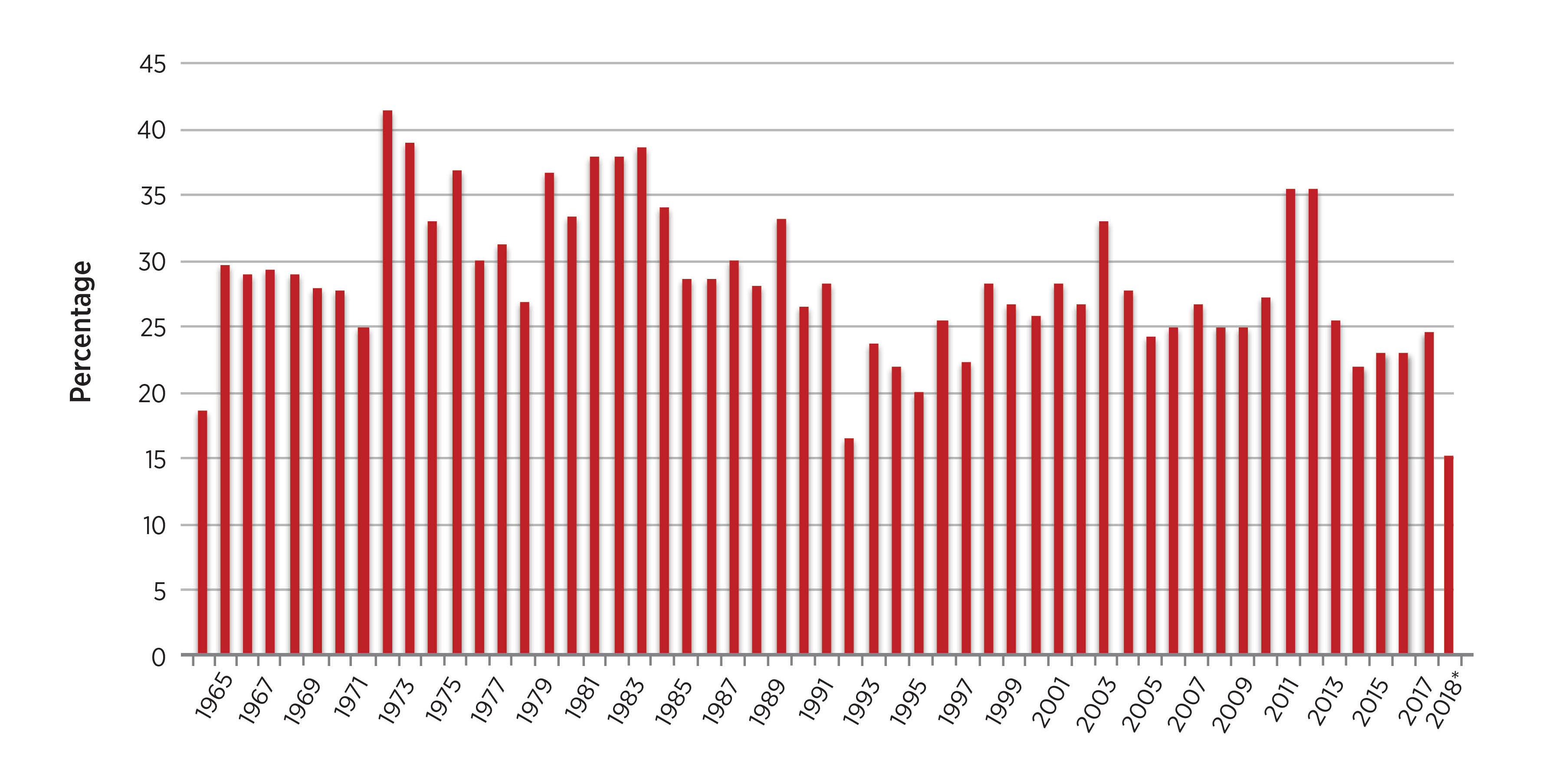

U.S. carrier strike group operational deployments from June 2017 to September 2018. The underways depicted do not note training exercises such as this year’s Rim of the Pacific exercise. USNI News Graphic

“This has all been building up over the last 17 years through overuse of the carrier force and naval aviation and a desire to have more forces ready,” former Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work told USNI News in a recent interview.

“When we kept two carriers in the Persian Gulf for a period of time, we kept telling the senior leadership that this was going to have a downstream effect, and it would really put a crimp maintenance-wise, and there would be gaps both in the Pacific as well as the Middle East. That is coming home to roost.”

Now, the service is breaking with almost 20 years of practice in where and for how long it sends its carrier strike groups. For example, the Navy hasn’t operated a carrier strike group in the Persian Gulf for six months and instead used the recent East Coast deployment of the Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Group to operate in the North Atlantic.

Officials say the moves are a signal to adversaries that the Navy is focused on high-end conflict, but at the same time, the new posture marks a significant break with decades of U.S. naval strategy that stressed the importance of almost constant presence in the world’s hot spots.

Dynamic Force Employment

Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John M. Richardson delivers remarks during the CNOs’ 23rd International Seapower Symposium (ISS) at the U.S. Naval War College on Sept. 19, 2018. US Navy Photo

In May, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson told reporters the Navy was starting to use a new deployment scheme based on Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis’ new National Defense Strategy mandate of operational unpredictability, called dynamic force employment.

When the Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Group got underway in April, it didn’t head for the Persian Gulf, where the U.S. has had a consistent carrier presence for decades.

Instead, USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75) and its escorts paid a quick visit to the Eastern Mediterranean to strike Islamic State forces in Syria, and then spent the rest of its short deployment operating with its British and French counterparts in the North Atlantic before returning to port unexpectedly after just three months deployed. Truman spent two months in port and returned to sea on Aug. 28.

“Secretary Mattis is deadly serious about this,” Work said. “He wants to be more operationally unpredictable, and the Truman deployment was supposed to be the poster boy for this.”

The Navy highlighted the unpredictable nature of the Truman deployment, but there is evidence the Navy is not making satisfactory progress catching up on deferred maintenance. On the East Coast, maintenance on USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) has already exceeded its expected six-month period and will extend into early next year, USNI News reported Monday. The delay, without other changes to schedules, pushes back the repair period of USS George H.W. Bush (CVN-77) for an indeterminate period.

Delays in carrier maintenance writ large has forced the Navy now to make choices in where it sends its forces, Bryan Clark, a senior fellow at the Center of Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, told USNI News in an interview last week.

Repair delays “created the need to reduce presence somewhere for the need to reset the force in the short term,” he said. “Dynamic force employment allowed them to reduce presence in the Persian Gulf and argued that it was to create more uncertainty for adversaries, and then they did these deployments to the Atlantic instead.”

USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) and USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75), the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Mason (DDG-87), attached to Destroyer Squadron (DESRON) 2, the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyers USS Forrest Sherman (DDG-98) and USS Arleigh Burke (DDG-51), attached to Destroyer Squadron (DESRON) 28; and the Ticonderoga-class guided-missile cruiser USS Normandy (CG-60) transit the Atlantic Ocean on Aug. 30, 2018. US Navy Photo

As part of the new dynamic force employment scheme, Mattis has also done more to temper the appetite of combatant commanders for constant naval presence and instead forced those commanders to think more strategically, Clark said.

Combatant commanders “get used to having a standard presence every day, and then they focus on security cooperation and training as opposed to thinking ‘I have to think strategically on how to counter Chinese and Russian gray zone activities’,” Clark said. “Maybe my dynamic force employment is a way to help uncertainty so China and Russia day-to-day don’t know what we might do.”

VCNO Moran said the COCOMs are learning to work inside the new boundaries of the strategy.

“Ultimately the Secretary of Defense is employing that force differently under this construct, and so this coordination has to occur,” he said. “What we’re seeing is there’s a blurring of the lines across COCOMs, which is healthy. They’re talking to each other, they understand that forces may be able to cross boundaries, so they have to work together with forces on either side of those boundaries–so boundaries are really kind of evaporating when it comes to how you operate the total force.”

Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. William Moran speaks to sailors and guests during an all hands call at Naval Station Norfolk, Va. on July 23, 2018. US Navy Photo

The new scheme has benefits for the Navy in the short term. Throttling back on the presence in the Middle East and Truman’s non-traditional deployment will buy time for the East Coast carriers to catch up in maintenance, Clark said.

However, while the trajectory of Navy readiness is improving, there are acute problems that will make improving the health of the aircraft carriers a challenge that will take decades to fix.

Navy Readiness Taxed

Lt. j.g. Morgan Dankanich, assigned to the amphibious assault ship USS Makin Island (LHD-8) work on repairs on Sept. 21, 2018. US Navy Photo

During the support operations of the ground wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Navy spent itself into a readiness deficit by using high-end weapon systems designed to take on peer adversaries against less sophisticated forces.

“I didn’t have a full appreciation for the size of the readiness hole, how deep it was, and how wide it was. It’s pretty amazing,” Secretary of the Navy Richard V. Spencer told reporters last month.

“You have a thoroughbred horse in the stable that you’re running in a race every single day. You cannot do that. Something’s going to happen eventually.”

When Mattis took the reigns of the Defense Department, he instituted a department-wide readiness drive with key investment in resetting forces, including almost $2 billon in supplemental readiness money in Fiscal Year 2017 to tackle almost 20 years of deferred maintenance on ships and aircraft.

Despite a boost in defense spending by the Trump administration, the backlog of ships now in line to be repaired after years of neglect are stressing the capacity of both the Navy’s public yards and the private yards who have been contracted to help clear the backlog of maintenance. Only 35 percent of ships in the private yards are coming out on time, and only about 45 to 50 percent are coming out on time from the public yards, Naval Sea Systems Command commander Vice Adm. Tom Moore said last week at the American Society of Naval Engineers (ASNE) Fleet Maintenance and Modernization Symposium.

“It’s important to keep in mind that I have 55 ships coming into maintenance availabilities in the private sector in 2019, and 2018 only 35 percent ships I have in availabilities are expected to move on time,” Moore said.

“Right now, we’re not delivering on everything we need delivered, and going forth we really need to deliver, and the pace of change is only going to get faster.”

2+3=?

USS Nimitz (CVN-68) transits the Persian Gulf, Oct 17, 2017. US Navy Photo

The Navy’s standard for strike group deployment has been the so-called two-plus-three model: two carrier strike groups deployed and three ready to surge with about a month’s notice.

That standard was developed in the early 2000s as part of the Fleet Response Plan championed by then-Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Vern Clark and mandated by then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.

The underpinnings of FRP and the subsequent Optimized FRP – championed by former U.S. Fleet Forces Command heads Adm. Bill Gortney and Adm. Phil Davidson – are based on the ability for the Navy to keep surge forces maintained and ready for a period of time after the deployment.

“The whole purpose of the Fleet Response Plan was to allow better surge readiness. In the late 1990s we were very, very stuck on the six-month deployment – and if you remember during Kosovo, during Operation Allied Freedom, there was a carrier in the Mediterranean, it did its six-month time hack, it’s time for them to come home. Everybody was going, ‘we’re in the middle of a war, how can you do this?’” Work said.

“So when Vern Clark came in, he said, ‘I want to be able to have more capability in surge. I want to have more carriers available.’”

However, the Navy burned through readiness and the potential ability to surge carriers was taxed by combatant commanders who expected a heavy carrier presence – especially in the Middle East. For example, then-Commander of U.S. Central Command Gen. Jim Mattis insisted on having two carrier strike groups in the Persian Gulf while he oversaw the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In addition to the use of the force, maintenance lapses in public yards exposed the fragility of the FRP scheme and left the service struggling to make the plan work without the necessary maintenance, CSBA’s Clark said.

“The problem was that readiness was expensive. The war with Iraq and Afghanistan created pressure on the budget, followed by sequestration, and it made it impossible to keep the readiness up during the non-deployed times. As a result, we ended up with FRP in name only,” Clark said. “Even in OFRP, we weren’t paying off the readiness.”

Carriers and the Public Yards

The service has been helped by the influx of readiness money to help fix the backlog of ships.

“The Navy’s increased readiness by funding ship operations, depot maintenance, aviation depot maintenance, spares, flying hours to 100 percent of the requirement, or whatever industry can take as an absorption level,” Navy Secretary Spencer said last month.

However, the service is facing problems money can’t solve – or at least solve quickly.

The single largest bottleneck to carrier deployments is the performance Navy’s four public shipyards – the only yards that are qualified to repair the service’s fleet of nuclear-powered carriers.

USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) prepares to pull into Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, Va. in 2017. US Navy Photo

Shortfalls in the public yards have been responsible for 1,300 lost operational days for aircraft carriers from 2000 to 2016, according to a 2017 Government Accountability Office report on the shipyards. That is the equivalent of seven six-month carrier strike group deployments. Just measuring from Fiscal Year 2015, the Navy lost the equivalent of a year of carrier availability due to maintenance overruns.

“The current capacity and capability of the shipyards’ drydocks will not support future operational needs,” reported the GAO in 2017.

“The Navy projects that the shipyards will be unable to support 73 – or about one-third – of 218 maintenance periods planned for the shipyards over the next 23 years, including five aircraft carrier and 50 submarine maintenance periods.”

The shipyards, some that predate the founding of the country, are plagued with antiquated infrastructure; a younger workforce that is just beginning to stabilize after years of layoffs, hiring freezes and retirements; and a lack of capacity to handle the number of ships the Navy needs to repair.

Capt. Kyle P. Higgins, commanding officer of the aircraft carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69), addresses the crew during an Aug. 18, 2018, all-hands call on the flight deck. Dwight D. Eisenhower is undergoing a planned incremental availability at Norfolk Naval Shipyard during the maintenance phase of the Optimized Fleet Response Plan. US Navy photo.

On Saturday, the commander of USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) announced to his crew and their families that the carrier would not leave the Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, Va., from a planned maintenance period until early next year. The decision will triple the length of the availability that was supposed to have ended in February. The delay will have a cascading effect on USS George H.W. Bush’s (CVN-77) repair period and could force the Navy to rethink its upcoming deployment schedules.

For a carrier strike group of 5,000 sailors, a minimum of five ships and up to 70 aircraft, the maintenance and training cycles are a complex matrix of individual and unit certifications that suffer when a maintenance period goes long.

“All of these things are a concert, and if you have any one part of that orchestra that’s not working, it’s not going to play that music well,” Rep. Rob Wittman (R-Va.), chairman of the House Armed Services seapower and projection forces subcommittee, told USNI News in an interview. “If you have a deployment that has to happen, it’s all of these ships that have to come together, it’s these squadrons, it’s the whole element of what happens with the carrier strike group. If you miss that, you miss days of availability for deployment, and that continues to reverberate and it pushes itself down the line and you have to make that up – and that’s where the Navy finds itself today.”

For its part, the service is optimistic of the ability of the public yards moving forward.

Earlier this month, the Navy announced a 20-year, $21-billion plan to get the public yards back on track, but it will be difficult for the public to track the progress: this year the Pentagon classified the number of operational days the carrier force lost due to lapses maintenance, citing operational security concerns.

How Much Does Presence Matter?

An F/A-18E Super Hornet assigned to the “Argonauts” of Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 147 flies over the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (CVN-68) in the Persian Gulf. US Navy Photo

A key tenet of Navy operations after the Korean War was constant U.S. naval presence in the world’s hot spots as a deterrent to aggression, with the carrier strike group as the most visible tool.

“There is no replacement for a carrier strike group in any phase of any kind of conflict. There are multiple examples of when a carrier strike group was put in place to deter,” then-Director of Air Warfare Rear Adm. Mike Manazir said during a House Armed Service readiness subcommittee hearing in 2015.

“Cuba in 1961. 1996, through the Taiwan Strait, two carrier strikers were sailed through there. The deterrence factor to the United States is significant. The carrier strike group, and no, sir, because of the resources the nation puts into the carrier strike group, which is not only the carrier but the five destroyers, cruisers that go with it and all the people that go into that, it is worth that deterrence factor.”

The reduction in deployment does come as the air war against the Islamic State has reached a nadir and the requirement for air power in the Middle East is far lower than at the height of conflicts of Afghanistan and Iraq. Naval aviation was key to U.S. airpower needs in the Middle East, with carrier-based strike fighters responsible for up to a third of air missions. That commitment put not only a strain on carriers but also the strike aircraft in the air wing.

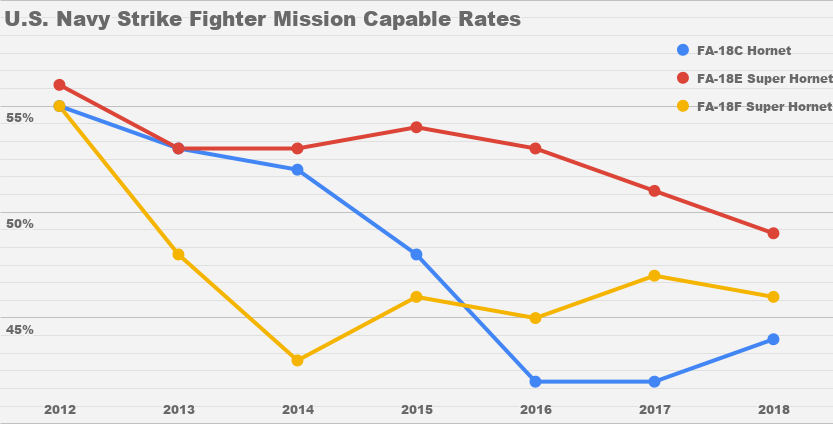

The Navy’s F/A-18E/F Super Hornet mission capable rates have been steadily declining since 2012, largely due to heavy use in support of Middle East operations. Less than half of the Super Hornet fleet is currently mission capable, according to Navy data obtained by USNI News.

“It’s not the just availability of the ship, it’s the availability of the squadrons. These aircraft have to go into maintenance, many time depot level maintenance. You can’t keep flying these aircraft at that rate,” Wittman said.

“We have to add more F/A-18 aircraft to the carrier fleet while at the same time we’re trying to ramp up and bring in F-35C into the inventory.”

USNI News Graphic

In the meantime, there has been a quiet shift in Middle East naval presence. There hasn’t been a carrier in the Persian Gulf since USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) left in March.

In September, almost a hundred Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy boats exercised in a rehearsal to block merchant traffic in the Strait of Hormuz. Instead of a carrier strike group being nearby, there was a single guided-missile destroyer and a handful of coastal patrol craft operating in the Gulf. And while the Russians conducted a massive naval exercise in the Mediterranean Sea earlier this month, the closest carrier strike group was on the other side of the Atlantic operating off the coast of Canada.

Navy leaders acknowledged that getting the force healthy would require choices for changes in how the Navy conducts its presence operations.

“When you’re resetting, there’s going to be tension, so the balance between those two things. How do you get a force ready to fight at the high end, and how do you reassure partners and allies on the other side? I think you can do both at the same time, but there’s going to be some working through this as we go,” VCNO Moran told USNI News.

“There are people who are perhaps a little concerned that there’s not a carrier in the Gulf right now, but there are other people in the [North Atlantic] that are delighted to see us back there because there’s other issues there as well, so I think we are trying to strike that balance.”

Clark told USNI News a key to the new reality of carrier presence was to clearly communicate with allies that things would be different.

German navy frigate FGS HESSEN (F 221) trails the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75) while transiting the Strait of Gibraltar on June 29, 2018. US Navy Phto

“There’s an advocacy component to this, where you have to explain to your allies that your presence and the posture you see day-to-day is going to change,” he said. “That’s not a reflection of us retreating. It’s not a reflection of our lack of credibility, but it’s part of our overall strategy. You have to explain the strategy and make it clear to them and they will also need to see the benefit that sometimes they get more presence than they would have in the past.”

For Wittman, the Navy and the Pentagon need to take care to signal to adversaries the U.S. strategic intention.

“I do think it’s a big deal because it’s key for us to have presence, especially these days. We watch the behavior of our adversaries get increasingly aggressive, and without presence there it could encourage our adversaries to be even more aggressive,” he said.

“Just a delay in a carrier deployment or presence in and of itself – if this were a first-time occurrence, I would say that it’s not that big a deal, but I think you have to look at it in the broader perspective. What’s led up to this?”

Eric Sayers, who previously served as a special assistant to the commander at U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and as a Senate Armed Services Committee staffer, said the troubles in carrier readiness should force the Navy to consider more presence missions that aren’t centered on a carrier strike group.

“I see an opportunity here for the Navy to have a conversation about how they bring significant combat capability to bear beyond the aircraft carrier,” he told USNI News this week. “Even when we don’t have a carrier sailing in the Gulf or the Pacific, we have other highly-capable destroyers, cruisers, attack submarines, and cruise-missile submarines forward-deployed globally performing a conventional deterrence mission for the nation. This often gets overlooked, as we are too quick to tally the days without a carrier deployed in a specific theater.”

180522-N-JT445-095

YOKOSUKA, Japan (May 22, 2018) The Arleigh Burke-class guided missile-destroyer USS Milius (DDG 69) arrives at U.S. Fleet Activities (FLEACT) Yokosuka, Japan on May 22, 2018. US Navy Photo

For Work, having a more lethal fighting force is worth small gaps in U.S. carrier presence.

“When people say ‘when you reduce your presence, something will happen,’ this is such a large dynamic world and this is such a small minor input, I just can’t imagine any country saying ‘I’m going to risk a war with the United States simply because they don’t have a carrier out right now,’” he told USNI News, referring to the 22-day gap in U.S. carrier presence this summer.

“If they’re going to risk a war with the United States, it’s going to be, ‘hey, we think we can win.’ And they may pick a time when it’s advantageous, but the lack of a carrier isn’t going to be the trigger in my view. There are a lot of people who say absence does send a signal; I just don’t buy it.”