An F/A-18E Super Hornet, assigned to the Stingers of Strike Fighter Attack Squadron (VFA) 113 flies over the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) on Oct. 26, 2017, in the Pacific Ocean. US Navy photo.

ABOARD USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT, IN THE PERSIAN GULF – After years of discussing and wargaming how the Navy would handle a fight against a peer or near-peer competitor, the Theodore Roosevelt Carrier Strike Group had a unique opportunity to practice a high-end fight at the start of its deployment.

As Russian and Chinese weapons systems are evolving – advanced anti-ship missiles, sensors, unmanned systems and more – the Navy’s pre-deployment training has gotten harder but still revolves around a linear progression of events meant to check off all the boxes of required skill sets for a deploying strike group. However, the Theodore Roosevelt Strike Group was given a chance to tackle a high-end adversary in an open-ended event, in a glimpse of how the U.S. Pacific Fleet could be looking at advancing tactics for a high-end conflict.

When the strike group departed San Diego in October, it was given a Fleet Problem to conduct during its transit to Hawaii. U.S. Pacific Fleet Command’s Adm. Scott Swift recently brought back the Fleet Problems series that dates back to the Interwar Period in the 1920s and 1930s, in an attempt to spur innovation in how the Navy creates and maintains sea control, as the admiral outlined in a March 2018 Proceedings magazine article.

TR Strike Group leadership told USNI News during a three-day visit to USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) and USS Bunker Hill (CG-52) that the Fleet Problem event, along with a particularly challenging set of pre-deployment training and certification events and a massive three-carrier exercise in the Sea of Japan, not only gave the crew a high degree of readiness for a high-end fight, but also a great level of confidence in their weapons and their ability to rise to whatever challenges they may face at sea.

Bunker Hill commanding officer Capt. Joe Cahill said among the challenges they faced in pre-deployment training was a Surface Warfare Advanced Tactical Training (SWATT), hosted by the Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center, that allowed for live missile shots and other types of high-end warfare events that hadn’t always been included in recent qualification exercises. Cahill said his crew fired 14 live missiles ahead of the deployment, whereas he had only participated in one live missile shot ever previously in his career.

“Every one of our teammates knows that the missile exercise that we executed was specifically designed to mirror potential areas where we would have to employ our weapons system in that manner when we were on deployment,” he said of the strike group deployment to U.S. 5th Fleet, with transits through U.S. 7th Fleet.

“We went and executed that against real targets with real missiles, and quite simply, we won. So from a practice standpoint, they saw it. So there’s a level of, in their hearts, it’s no longer, hey, trust us, this will work. They heard the missile go whoosh, they saw it go boom.”

The Fleet Problem

A Phalanx Close-In Weapons System fires during a live-fire exercise aboard the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) during its transit from San Diego to Hawaii, on Oct. 9, 2017. US Navy photo.

Theodore Roosevelt Commanding Officer Capt. Carlos Sardiello told USNI News the Fleet Problem event was much different than the highly scripted Composite Training Unit Exercise (COMPTUEX) typically considered the pinnacle of high-end warfighting events for a deploying unit.

The Fleet Problem, which asked the TR CSG to get from San Diego to Hawaii while either avoiding or taking out red force submarines, surface ships and other threats, was completely open-ended. In Swift’s Proceedings article, he noted that, rather than ask the strike group to conduct anti-submarine warfare – which is what would happen during COMPTUEX – he asks the strike group to conduct a long-range strike in an environment full of enemy submarines.

“The CSG’s mission would not be ASW, but rather conducting a core combat mission (strike) in support of the joint fight in a robust submarine threat environment,” Swift wrote.

“Managing the submarine threat is the means to the end – strike. If you destroyed all enemy submarines and lost no friendly units but were unable to execute the mission assigned – strike – then Blue loses and Red wins. How the CSG commander manages that threat to accomplish the mission is not prescribed. Speed and maneuver? Go for it. Aggressive surface ASW? Great. Will the escorts sweep ahead or stay near the CSG? Air assets? Of course. How is that coordination going?”

The Theodore Roosevelt CSG leadership said they loved that freedom to dictate their own path forward.

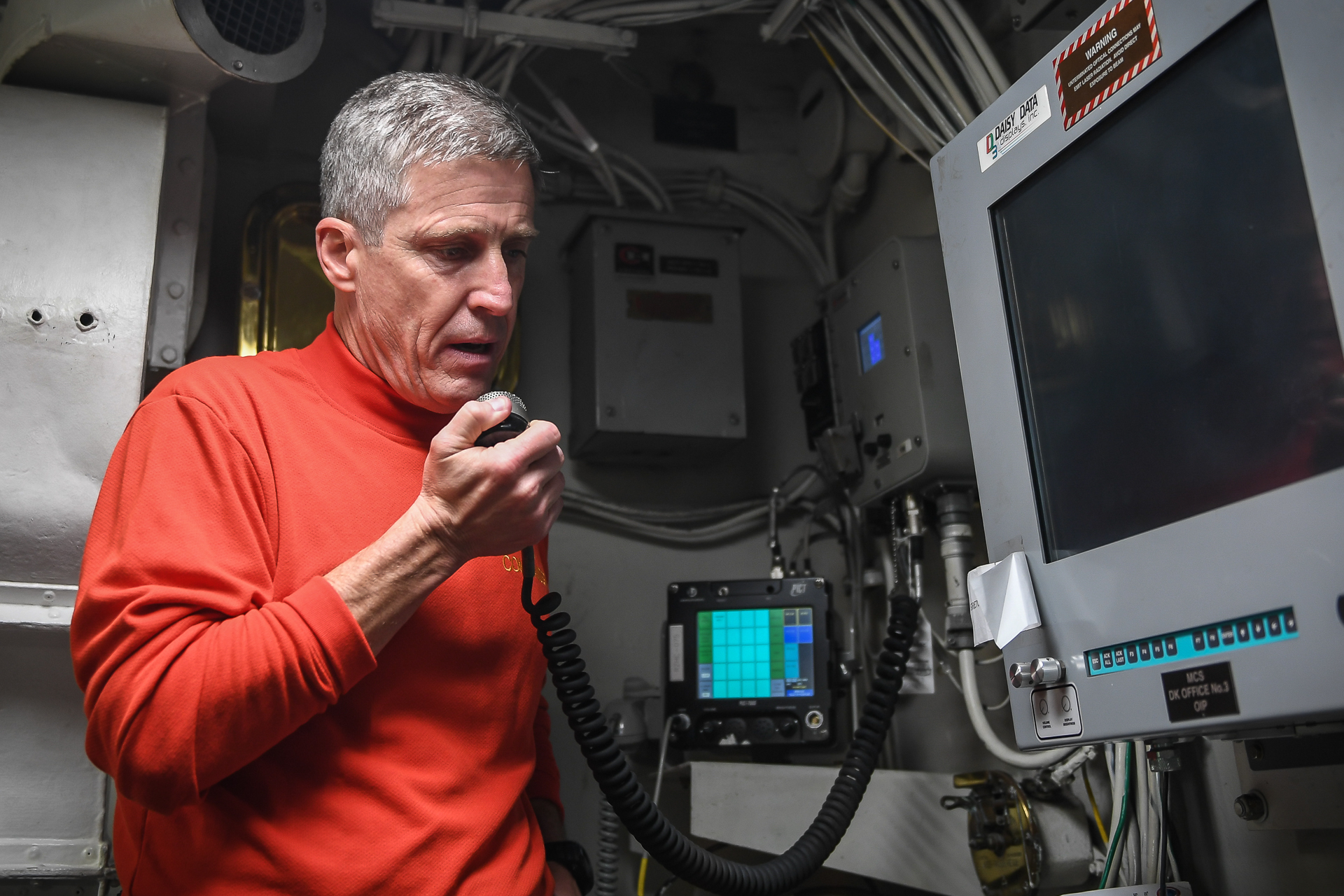

Capt. Carlos Sardiello, commanding officer of the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71), addresses Sailors during a frocking ceremony on the ship’s flight deck. US Navy Photo

“We employed the strike group to the limit of our experience and understanding of our capabilities to execute the mission. And with real adversaries out there, (opposition forces) being played by Pacific Fleet assets, not only Navy but full spectrum other assets that might be applied by a potential adversary,” Sardiello said.

“Whereas COMPTUEX was good training for all the different mission sets we would see, it wasn’t open-ended and unlimited in scope. And so the unpredictability, the fog of war required us to work closely together to adapt to the threat and make decisions. We did some long-range strikes out there – at one point we had a wall of 14 fighters, each with two Harpoons apiece, going way beyond the horizon and striking against potential surface adversaries. That, I don’t think that’s been done in recent history, we were in the middle of nowhere and then we had to recover these aircraft, all of them, after this long-range strike.”

Additionally, Destroyer Squadron 23 Commodore Capt. Bill Daly told USNI News that the exercise was a great opportunity for surface warfare officers to learn to work with and employ an air wing for sea control. His surveillance watch team, which directs both ships and aircraft in the strike group to seek out the enemy and recommend strikes before the enemy can find the CSG, was able to get live practice in a high-threat environment during the transit to Hawaii.

“War at sea … is nothing notional anymore. It’s executed, it’s repeated, and so we did that during that high-end training,” Daly said.

“And that is a big deal for surface warfare officers to learn how to employ and interact with an air wing, to conduct a war-at-sea strike.”

In summary, Sardiello described the event as “(emissions control) operating environment, blue water ops, a large number of strike fighters going to the limit of their range, all that – it doesn’t get any more real than that in a Pacific Fleet fight,” he said.

“These things we were doing were on the edge, the limitation of our capabilities and our tactics.”

After the event, Rear Adm. Victorino Mercado, director of maritime operations for PACFLEET, did a hot wash with the strike group to go over the decisions they made and how effective they proved. CNA also did an analysis of the event that will help inform future exercises, Sardiello said.

Carrier Strike Group 9/TR CSG Commander Rear Adm. Steve Koehler told USNI News that the Fleet Problem event was an extra benefit to the CSG after the pre-deployment training and certification due to it being “a complete free-play high-end event.”

“In [traditional] high-end fight training, we still have to get to a certain level of, are you proficient at this particular thing,” he said of COMPTUEX. With the Fleet Problem, though, “it was, go get them. What it did for the crew, to be perfectly honest … was it gave them the confidence that what they were taught in the training piece works, and it generated a whole different level of competence and confidence, both, that is awesome,” Koehler said.

Rear Adm. Steve Koehler, commander, Carrier Strike Group (CSG) 9, addresses the crew during 2017 Thanksgiving dinner aboard the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71). US Navy Photo

“You can’t get anywhere without the blocking and tackling piece, you’ve got to be really good at that, but you can’t quit at that. You have to then tactically stretch yourself, put enough risk management in there so you can push people harder than they want. The bottom line is that the high-end fight requires everybody to be outside of their entire comfort zone, so if you don’t push them in the training environment you’ll never get there,” the admiral continued.

“And the whole goal of the high-end fight, in my opinion, both the COMPTUEX and then this Fleet Problem, generates a mindset that, instead of, ‘oh my gosh I can’t do it,’ which is where it starts now with everybody at the leadership level –the O-5s have never done this, so they have grown up in a non-high-end threat level environment; they’ve grown up in precision strike and a very very difficult things like we’re seeing in Syria, but they have not grown up in a sea control defensive and offensive fight and being able to do it. So you have to show them they can do it. Once you show them, then the young people will say, ‘oh, that’s what we do now.’”

Three-Carrier Strike Force Operations

The aircraft carriers USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76), USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) and USS Nimitz (CVN 68) and their strike groups are underway, conducting operations in international waters as part of a three-carrier strike force exercise on Nov. 12, 2017. US Navy photo.

In addition to working at the higher end of warfighting skills, the TR CSG also got to work at a larger scale – participating in a three-carrier operation in the Sea of Japan during the transit through 7th Fleet.

Sardiello called this carrier strike force-level event “a good exercise, but limited in scope due to where we were” – chiefly, in sight of Chinese forces. He said the Navy could not practice certain high-end tactics and procedures there, but it was a good opportunity to practice command and control of a three carrier strike force. Rather than have three strike group commanders, three air defense commanders, three sea control commanders, and so on, the roles were randomly “dealt out like a pack of cards” throughout the three strike groups. All the top leadership within the TR CSG said the operation went exceptionally smoothly, a testament to the interoperable and scalable nature of the carrier strike group command and control structure.

Still, Sardiello said he sees the future of Navy training and operations as a melding of the two events in which is strike group participated: high-end warfare at the carrier strike force level. He said he’s pushing for development of carrier strike force tactics for major combat operations against a near-peer adversary, which need to be developed and practiced for future strike group deployments.

“We were raised, folks my age and older, against a Cold War adversary, against a very capable USSR Navy and fighting at sea, open ocean; that’s how we were raised. And we understood the risks and the tactics, and we practiced that endlessly,” he said.

“We’ve kind of gotten away from that in the past 20-some years, and now it’s coming back and the Navy’s kind of rediscovering, reemphasizing that mission set because the threat is slowly increasing.”

The Future Fight v. The Current Fight

An F/A-18E Super Hornet from Strike Fighter Squadron VFA) 113 launches from carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt on March 10, 2018, in the Persian Gulf. USNI News photo.

Even as ship and strike group leadership embraces the opportunity to train to the future fight, they still have to contend with the realities of today’s operations. Both Sardiello and Koehler talked about the challenges of conducting high-end warfighting events at the beginning of the deployment, only to spend the bulk of the deployment in 5th Fleet – a challenging area due to the complex airspace over Syria, but one that prioritizes air-to-ground warfare skills more than sea control or other high-end skills – and then have to transit back through 7th Fleet where leadership worries the crew may need those advanced skills again.

“It’s a challenge to maintain readiness during deployment when you’re so focused on one mission area,” Sardiello said.

“Part of our overhead goes into defense of the carrier: that’s going to be control of where we are in the Arabian Gulf. And then the lion’s share of what we’re trying to do is project power in support of the ground operations where we’re being told, and that’s [Operation Inherent Resolve in Iraq and Syria] and [Operation Freedom’s Sentinel]; mostly OIR. That’s our bread and butter. On the margins, that extra loading, we’re doing a little bit of that high-end tactics training each day, but it’s not sustainable to be highly proficient. So prior to getting back to 7th (Fleet), we have a couple days planned dedicated and then along the way we’re going to get back up on step for that mission set. They’re different; when we get to 7th, it’s not this high-end kinetic fight with weapons-dropping, it is presence operations in close proximity to highly capable military forces, and we want to make sure there is no miscalculation and we all operate safely in international waters and don’t put ourselves at risk by being down on our tactics.”

Koehler agreed, saying that after advanced warfare training in the Pacific, they chopped into 5th Fleet and “it’s a different fight. The tactical fight that the aircrew are doing is probably some of the most complex fighting (in the sense that) the threat picture in Syria is just crazy: how many different countries can you cram in one different place, where they all have a different little bit of an agenda, and you put a tactical pilot up there and he or she has to employ ordnance or make defensive counter-air decisions with multiple people – Russians, Syrians, Turks, ISIS, United States, all these things are happening, and that complex battle space is really hard. So sometimes we talk about the high-end fight – but it’s not that, it’s different. And so the high-end fight skillset has degraded, which doesn’t mean that the skillset of the pilots or the ship drivers and all the stuff here aren’t executing very well – but the high-end piece has degraded. So I want to hit some of that training and be ready to go” for the transit back home.

Koehler added that the threat picture in the Mediterranean Sea for East Coast strike groups sailing to and from 5th Fleet isn’t any easier than the transit through the Pacific: an increase in Russian submarine and surface combatant activity there also requires readiness at the high end of the warfare spectrum. Prior to chopping out of 5th Fleet, he said, it would be important for CSGs to find a few days to revisit the advanced warfare skills the sailors may not have used since arriving in the Persian Gulf months ago.

“If we continue to come to 5th fleet, we have to remember, in my opinion, that we’ve got to fight home too,” the admiral said.