The mighty ships of the German High Seas Fleet were scuttled by their own sailors in Scapa Flow in Orkney on 21 June 1919. A newly discovered letter paints an extraordinary picture.

It was the single greatest loss of warships in history, and the sailors killed that day were the last fatalities of World War One.

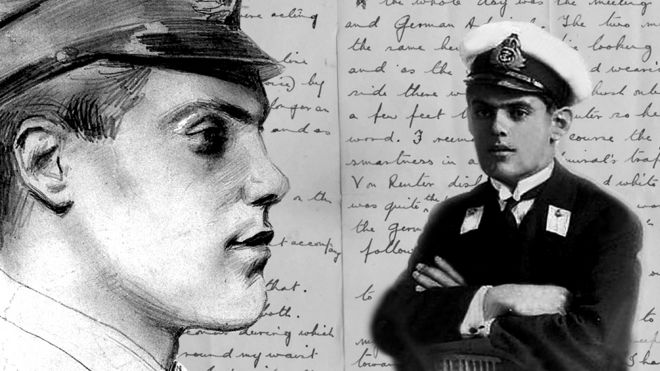

One young British officer not only witnessed the astonishing events, but recorded his own dramatic involvement in an account which has remained unpublished until now.

Edward Hugh Markham David – Hugh, or “Ti” (short for “Tiny”) to his family – was 18 years old in 1919, but had already been in the Royal Navy for two years.

By June he was a sub-lieutenant aboard the battleship HMS Revenge, flagship of Admiral Sir Sydney Fremantle.

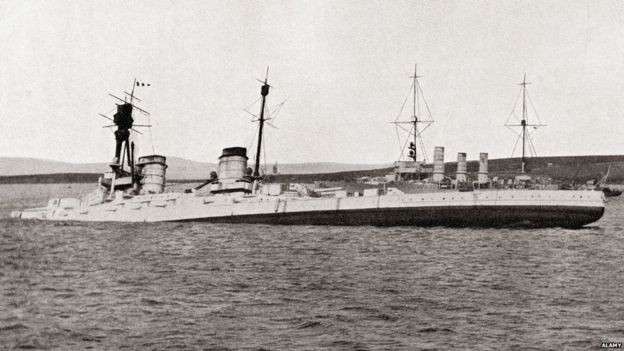

Fremantle was the man charged with guarding the interned ships of the German High Seas Fleet in the Orkney anchorage of Scapa Flow.

On the morning of Sunday 21 June, the British fleet steamed out on exercise. Hundreds of miles away, in Paris, the wrangles over the peace treaty to officially end the Great War were reaching a climax. The fate of the magnificent German warships was due to be decided.

The German commander, Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, believed that his ships were about to be seized as spoils of war and divided up between the victorious Allies. He felt duty-bound not to let that happen.

At 10:30 von Reuter’s flagship, Emden, sent out the seemingly innocuous message – “Paragraph Eleven; confirm”. It was a code ordering his men to scuttle their own ships.

Beneath decks, German sailors immediately began to open seacocks – valves that allow water in – and smash pipes.

There have been many accounts of the drama that followed, but Hugh David’s version of events has never been published.

My Dearest Mummie, I am writing this at sea, after witnessing perhaps the grimmest and certainly the most pathetic incident of the whole war…”

David wrote the very next day to his mother from HMS Revenge, as the battleship steamed south to Cromarty, loaded with German sailors, now prisoners-of-war.

Even after nearly a century, the words are clear. So too are the feelings of the young man. In the emotion of telling his story, David got the date of his letter wrong – recording it as 26 June instead of 22 June.

HMS Revenge received a message at around 12:45 on 21 June that its captive German ships were sinking. The fleet turned back at full speed. It was too late.

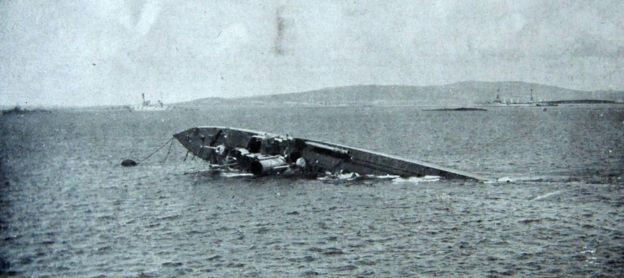

“The sight that met our gaze as we rounded the Island of Flotta is absolutely indescribable,” wrote David.

“A good half of the German fleet had already disappeared, the water was one mass of wreckage of every description, boats, carley floats, chairs, tables and human beings, and the ‘Bayern’ the largest German battleship, her bow reared vertically out of the water was in the act of crashing finally bottomwards, which she did a few seconds later, in a cloud of smoke bursting her boilers as she went.”

The Germans took to small boats to escape their sinking ships. From one of them Admiral von Reuter was taken aboard HMS Revenge.

“About the most dramatic moment of the whole day was the meeting of the English and German Admirals,” wrote David. “The two men were about the same height, both fine looking and tall.”

As the German climbed wearily over the side there was a deadly hush on board. I was a few feet behind von Reuter so heard every word…”

Although von Reuter later recalled this conversation in his memoirs, David’s record appears to be the only contemporaneous one:

“At first there was a pause, the German standing at the salute then the following conversation –

Fremantle: I presume you have come to surrender?

Von Reuter: I have come to surrender my men and myself (with a sweeping gesture towards the fast sinking ships) I have nudding else.

Pause

Von Reuter: I take upon myself the whole responsibility of this, it is nothing to do with my officers and men – they were acting under my orders.

Fremantle: I suppose you realise that by this act of treachery [hissing voice] by this act of base treachery you are no longer an interned enemy but my prisoner of war and as such will be treated.

Von Reuter: I understand perfectly.

Fremantle: I request you remain on the upper deck until I can dispose of you.

Von Reuter: May my Flag Lieutenant accompany me?

Fremantle: Yes, I grant you that.

The drama recorded by David took place at about 16:00 that Midsummer Day. It seems David was then ordered to join a boarding party to try to save the few German ships still afloat.

“I strapped a revolver round my waist grabbed some ammunition and leapt into the drifter with an armed guard and took off to save the Hindenburg,” wrote David.

The Hindenburg was the biggest German battlecruiser. She sank as Hugh’s small boat drew alongside but before he climbed on board “very nearly taking us with her.”

David’s launch turned instead for the giant battleship Baden, sister of the Bayern. She was the only German battleship the Royal Navy succeeded in saving.

“We then got alongside ‘Baden’ who was going down fast and hurried below to see what we could do to save her – we closed watertight doors which kept her up temporarily but she eventually had to be towed ashore,” explained David.

“We found one little German sub-lieut (sic) below who was dragged onto the upper deck.”

The flag captain told him he would be shot at sunset if he did not immediately take us below and show us how to shut off the valves…”

The German said that he didn’t mind if he was shot straight away. David, however, doesn’t record whether the unfortunate man was shot, but there’s no doubt that others were. They were the final casualties of World War One – the Treaty of Versailles was signed a week later on 28 June 1919.

“The terrible part of the whole show, to my mind, was that the Huns hadn’t got a weapon between them and it was our bounden duty to fire on them to get them back to close their valves,” wrote David. He describes the British as being in an “awful position”.

It was quite obvious that the huns would die to a man rather than save their ships so that there was no point in going on firing – yet what could we do?”

Andrew Choong, Curator of Ships, Plans and Historic Photographs at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, has read a transcript of David’s letter.

“I think it’s an absolutely fascinating account. Our knowledge and analysis of this event are based on the recollections of the great and the good, like von Reuter and official reports. I haven’t ever seen an account of a similar experience. Here’s a mid-level officer placed right in the middle of it all.”

Choong was struck by David’s feelings. “Here is a man who comes across first as a human being and is obviously very uncomfortable about the whole thing,” he says.

“I think it’s very moving because there is no relish in what he’s doing and he finds time to mark the acts of German bravery. It’s a remarkable document.”

After his eventual return to Germany, von Reuter help put together a government report on “British breaches of international law” against the German sailors, charges consistently denied by Britain.

Choong says the British would have had justification to fire in some cases. “The rules of engagement were that if you saw a German opening a seacock or giving orders to others to do so you could order him to stop – and if he refused, you could shoot him,” he says.

However, there’s evidence, including in David’s letter and a subsequent one he wrote a few days later to his Uncle Walter, to suggest some British sailors went further, firing on Germans who were trying to escape from their sinking ships.

“Today you would say there’s probably no excuse, but that’s to impose a modern view of the situation which then was very unclear and very uncertain,” says Choong. “In one or two places in the letter it makes it sound like a bit of a massacre but in fact only nine men were killed and 16 wounded out of hundreds and hundreds.”

The tumultuous events of that day clearly had their effect on Hugh David.

I have seen men killed for the first time in my life and at that without the crash of action to keep ones spirits up, and it has made me think, God, it has made me think…”

He died in 1957. His letter to his mother eventually passed to his daughter, Hilary Chiswell Jones. It was her decision to make it public, after 96 years.

“I probably didn’t read it until I was 25 or so,” explains Hilary. “I remember being impressed by the way he portrayed the event and also by his awareness of how awful it was for the Germans.

“He obviously had compassion for them and I admired him for it – I was pleased he showed it, especially at 18, when you tend to be perhaps a bit cocky. I thought that showed his humanity.”

Does she think her father did fire on the German sailors?

“I think he would have told his Uncle Walter in his letter to him had he shot anyone, so I don’t think so.”

Within months of the scuttling, David had left the Royal Navy. He joined the fledgling RAF, where he served with distinction until 1950, rising to the rank of Group Captain.

But it seems unlikely he ever forgot the extraordinary things he witnessed at Scapa Flow.

More from the Magazine

Armistice Day is remembered as the day World War One ended, but for naval historians Britain’s greatest victory came 10 days later. Operation ZZ was the code name for the surrender of Germany’s mighty navy.

For those who witnessed “Der Tag” or “The Day” it was a sight they would never forget – the greatest gathering of warships the world had ever witnessed.