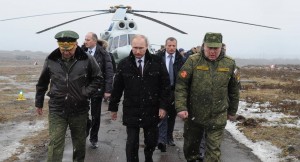

Vladimir Putin and the Lessons of 1938

He’s not Hitler. But we’ve got to stop him all the same.

By GARRY KASPAROV –

t’s been a busy few weeks for Vladimir Putin. In the last month, the Russian president has hosted the Olympic Games, invaded a neighboring country and massed troops along its border. Back in Moscow, the Kremlin has cranked up the volume of hysterical anti-Western propaganda to a roar while cracking down on the last vestiges of the free media. All the while, he proclaims he wants peace and accuses Western leaders of hypocrisy and anti-Russian sentiment. If Putin wanted to do a better imitation of Adolf Hitler circa 1936-1938, he would have to grow a little mustache. Equally troubling is that the leaders of Europe and the United States have been doing a similarly good impersonation of the weak-kneed and risk-averse leaders who enabled Hitler’s rise in the 1930s.

I know full well that any mention of the maniacal Nazi leader is viewed as being in poor taste by many. The good news is that it took many years for the West to finally admit that Putin is a dictator and only a few weeks for respected public figures such as Hillary Clinton to acknowledge how closely he is following in Hitler’s footsteps right now. Nobody except the most naked of Kremlin apologists is debating whether Putin’s anything but a tyrant anymore. Instead, we’re searching for the right historical analogy: Is it Budapest 1956? Prague 1968? Austria 1938?

To which I say: Welcome to the club! It remains to be seen, however, if the media figures and politicians who have so quickly adopted my Anschluss rhetoric are willing and able to do what is necessary to stop repeating the past. In recent days, the United States and several European governments have bolstered their statements, which will, I hope, now be followed up with strong sanctions and other steps to ostracize and deter Putin.

Over the past nine years I have dedicated most of my life to opposing Vladimir Putin’s campaign to destroy democracy and civil liberties in Russia. My efforts have included everything from marching in the streets of Moscow to traveling to nearly every Russian province to sounding the alarm about the true nature of Putin’s regime as widely and loudly as possible. Eight years ago, my main arguments to international audiences were about the myths of Putin’s Russia. I explained over and over that no, Putin wasn’t really a democratically elected leader; our elections were a stage-managed charade. That yes, he really was a bad guy who was supporting rogue states abroad while in Russia he was persecuting dissidents, locking down the media under state control and subordinating the Russian economy to the Kremlin and his small circle of cronies. And if Putin is really so popular in Russia, I asked, why is he so afraid of fair elections and a free media? For this, many in the West dismissed me as a fringe troublemaker who might potentially usurp their narrative of how engagement with Putin’s Russia was going to bring about reform and liberalization.

Although I accurately saw Putin’s main advantage over his Soviet predecessors—open access to international markets and institutions—I never imagined he would abuse and exploit them so easily, or that Western leaders would be so cooperative in allowing him to do so. Putin’s oligarchs bank in London, party in the Alps and buy penthouses in New York and Miami, all while looting Russia under the auspices of a reborn KGB police state. It’s “rule like Stalin, live like Trump.” The West has fulfilled every cynical expectation Putin had about how easy it would be to buy his way around any nasty confrontation over human rights. Even now, with Russian troops occupying Crimea in preparation for annexation, European countries are terrified of losing any Russian oligarch money. They are afraid of using the very thing that gives them so much potential leverage over Putin—exactly as he hoped.

Of course Putin isn’t Hitler, although his potential for devastation is even greater due to a massive nuclear arsenal under the control of what appears to be a shrinking and desperate inner circle. I would never minimize the horror of the Holocaust, the millions of war dead or the heroism of those who defeated the Nazis. My goal is to scrutinize how the rest of the world did and did not respond while Hitler the popular German statesman was becoming Hitler the monster in the 1930s. Today’s dictators are not so averse to learning from their predecessors. Putin imitating Hitler’s 1936 propaganda methods and Hitler’s 1938 invasion tactics does not mean he will also declare a new Reich and head straight for Poland. But we should draw lessons from that history, too.

When I tweeted about the possibility of a “Ukrainian Anschluss” on Feb. 20, the Sochi Games were still underway. I noted that Putin’s invasion of Georgia took place during the Beijing Olympiad in 2008 and wondered what would dissuade him from similar action in Ukraine since Russian troops still occupy South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Georgian territories, with no visible harm to Putin’s international relations. By the way, Russia was never sanctioned by the European or the United States over Georgia, and just a few months after the brief war ended the EU restarted talks with Russia on a formal partnership and cooperation agreement. It was quite high-minded of them, but when dealing with Putin, turning the other cheek just gets you slapped again.

A week or so later, to my surprise, “Anschluss” was on the front page of a Polish newspaper and on the lips of Hillary Clinton. And yet, those who oppose taking any serious action against Putin’s invasion of Crimea still enjoy scoffing at the now-obvious parallels with Hitler’s seizure of Austria and the Czech Sudetenland. It’s a hard habit to break, apparently.

It’s one thing for academics and pundits to calmly sympathize with Putin and his “vital interests” and his “sphere of influence,” as if 50 million Ukrainians should have no say in the matter. It’s quite another thing for Barack Obama, David Cameron and Angela Merkel to fret about the “instability” and “high costs” caused by sanctions against Russia—as if that could be worse than the instability caused by the partial annexation of a European country by a nuclear dictatorship, carried out with impunity.

This debate, too, has a Nazi-era parallel, and fittingly enough it was about money and centered in London, or “Moscow on the Thames,” as many call it now due to the number of wealthy Russians who park their assets in British banks and real estate. But it begins in another favored oligarch destination: Switzerland. In my informal survey of knowledgeable friends, few had even heard of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). This “bank of central banks,” still based in Basel and founded in 1930, is the sort of shadowy institution that now regularly appears as a villain in Hollywood movies. It is well worth reading up on the remarkable story of how the BIS continued to operate during the war, with a board and staff composed of representatives of both Allied and Axis nations and presided over by an American. I will limit myself to one remarkable true tale, that of 23 tons of Czech gold.

The Czechs, seeing the writing on the wall, had transferred almost all their gold reserves outside of the country for safekeeping by 1939. Some went to Basel, and 1845 bars of it, worth six million 1939 British pounds, or nearly $400 million in today’s dollars, went to the Bank of England in London. Just days after the Nazis took Prague, on March 18, two bank-transfer requests quickly went out. (Literally at gunpoint, it was later revealed.) One for the 23.1 tons of Czech gold held with the BIS at the Bank of London, to be moved to the Reichsbank’s account. The other for 26.8 tons held by the Czechoslovak National Bank in London. The second transfer did not take place, as the Bank of England followed the new law freezing Czech assets in Britain.

But the BIS emptied the Czech account of the 23.1 tons and just a few days after that, the Reichsbank moved the gold via transfers and then physically to its vaults in Berlin. It took weeks before the British and French press got wind of the story, and the outrage was far too late in coming to do anything about it. Then in June, a remarkable discussion took place in the British House of Commons, when a bill was introduced to oblige the Bank of England to consult with the government on any issue affecting national interests.

As obvious as this measure may sound, the bill went down to defeat 125-196—and this in June of 1939, only months before Hitler’s invasion of Poland! Sir Herbert Williams spoke for the No camp. “[MP Strauss, the bill’s sponsor] is merely denouncing the Government and the Bank of England and Herr Hitler and some other people, which is always pleasant to do,” he said. “[B]ut it is very foolish to allow yourself to be irritated because of a particular transaction. It might lead you into a great mess later on.” A great mess indeed. Winston Churchill was more on point, saying in the House that it would be difficult to get people to enlist in the military when the administration itself was “so butter-fingered that six million pounds of gold can be transferred to the Nazi government!”

This obscure story struck a chord with me when I first came across it in 2009 in a Russian article on the history of the morally agnostic global banking system. It reminded me of the countless deals struck by Putin and his oligarch allies all across Europe, and how the governments that could enforce their own corruption laws so often look the other way. When the oil magnate and dissident Mikhail Khodorkovsky was jailed and his company Yukos dismembered and sold to Putin’s friends at the state company Rosneft, the guarantees and IPO were all underwritten and coordinated by big brand-name Western banks and agencies, giving Putin and his clique the legitimacy and hard cash they need to stay in power.

And yet today many leaders and pundits alike cry about their lack of leverage over Russia, and how unfair it is to “denounce Herr Putin” over a tiny peninsula when many billions of dollars are at stake. Staying on good terms with Russia is not important to them, but they are very concerned about staying on the most intimate terms with Russian money. They have all the leverage in the world, if only they have the courage to use it. German Chancellor Angela Merkel approached the right level of urgency on Thursday, when she rallied German business leaders for sanctions and warned of the “massive economic and political harm” that would come to Russia should Putin not abandon his ambitions in Ukraine.

Putin is no master strategist. He’s an aggressive poker player facing weak opposition from a Western world that has become so risk-averse that it would rather fold than call any bluff, no matter how good its cards are. In the end, Putin is a Russian problem, of course, and Russians must deal with how to remove him. He and his repressive regime, however, are supported directly and indirectly by the free world due to this one-way engagement policy. Putin is no Hitler, and there will never be another. But we cannot forget the harsh lessons Hitler taught us about the fatal dangers of appeasing a dictator, of disunity in the face of aggression and of greedily grabbing at an ephemeral peace while guaranteeing a

Back to Top