The flight deck crew of USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) launches and recovers F/A-18E-F Super Hornets from Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 122 as pilots in the West Coast fleet replacement squadron conduct carrier qualifications on March 9, 2021. USNI News photo.

ABOARD AIRCRAFT CARRIER USS GERALD R. FORD, IN THE ATLANTIC OCEAN – When new commanding officer Capt. Paul Lanzilotta wakes up each morning on USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78), his long and diverse to-do list highlights the balance the aircraft carrier is trying to strike as it wraps up its new-ship testing and prepares for shock trials this summer, while also carrying out other duties as the only available aircraft carrier on the East Coast.

Lanzilotta is overseeing dozens of contractors from Newport News Shipbuilding who are completing the Advanced Weapons Elevators and conducting other maintenance work. Wires are already going up around the ship to connect sensors and data-collection systems ahead of the explosive shock trials, where the Navy will set off a bomb in the water near the new warship and measure how well it could take a hit. And the team is conducting the first at-sea phase of its Combat Systems Ship Qualification Trials (CSSQT), where the new ship will test its unique network of self-defense radars, combat systems and weapons – with the aim of preventing the ship from taking a hit in combat at all.

At the same time, Lanzilotta is the only carrier captain at sea on the entire East Coast, meaning he has a responsibility to help train sailors from other Virginia-based carriers that are in maintenance, as well as conduct carrier qualifications for new pilots in flight school and in fleet replacement squadrons.

Despite so many activities happening in parallel, Lanzilotta said all are going well.

Proving Out Ford-Class Efficiencies

The flight deck crew of USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) launches and recovers F/A-18E-F Super Hornets from Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 122 as pilots in the West Coast fleet replacement squadron conduct carrier qualifications on March 9, 2021. USNI News photo.

Part of what’s driving the length of Ford’s post-delivery test and trials period, including its ongoing CSSQT, is the large number of new systems on the carrier compared to the Nimitz-class carriers already in the fleet. The ultimate goal of these new systems was to help the Ford class generate more sorties and be more lethal while having a smaller crew.

Lanzilotta told USNI News during the March 9 visit to the carrier that the efficiencies will all culminate in a greater sortie-generation once the ship actually starts conducting normal carrier air wing operations – though that hasn’t happened yet. The ship can’t boast that it achieved a certain-percent-greater sortie-generation rate than its legacy counterparts, Lanzilotta said, until full CVW operations take place, but he’s already seeing bits and pieces of greater efficiency in everything the ship is doing.

Though the ship hasn’t worked with a full carrier air wing yet to do cyclic flight operations and see how fast the new Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS) can clear all the planes off the flight deck, he said EMALS is proving its worth already on the maintenance side.

“Any complex system requires constant attention and maintenance. And the steam catapult system obviously still serving today overseas, deployed, doing the work of the republic every single day (on the Nimitz-class carriers), that requires a lot of manpower and a lot of man hours and woman hours on the flight deck. When we stop flying here at the end of the day – so last night we finished – I don’t know, XO: what was it, midnight-30? Almost one in the morning? On a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier, you would then have two to three hours of preventative maintenance to do on all that kit before you can close up shop for the night and get a bite to eat and get some rest for the next day of flight operations. On this ship, our sailors literally put (EMALS) in standby mode, and get the same bite to eat and go to bed. Those are hard-to-measure benefits, but in my mind they’re huge,” Lanzilotta said.

On the new Dual-Band Radar – which the Navy is replacing with the Enterprise Air Surveillance Radar (EASR) for future carriers, meaning Ford will have a unique combat system setup – Lanzilotta said the radar is up and running for CSSQT and was tracking planes all morning, including the C-2A Greyhound that brought reporters from Naval Air Station Oceana to the ship about 100 miles out to sea. The CO said the radar tracked the C-2 and several Leer jet practice targets at great distances all morning and that, as an E-2 Hawkeye naval flight officer whose job revolves around good radar systems, he was very impressed with DBR’s performance. Importantly, he added, it hadn’t had a failure in the month since he took command of the ship.

“Again, the things you’re not seeing: What are you not seeing? You’re not seeing us taking it down in the middle of the night to do maintenance on the antenna. You’re not seeing us replace the power modules that we’ve got in the older radars and stuff like that. So I’ve been very impressed thus far” with DBR, he said.

Sailors assigned to USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) load equipment onto an advanced weapons elevator in Ford’s hangar bay, March 7, 2021. Ford is underway in the Atlantic Ocean conducting an independent steaming event. US Navy photo.

The 11 Advanced Weapons Elevators have remained a lingering problem for the ship and have been the focus of several hearings with lawmakers in Congress. Lanzilotta said the seventh was delivered to the crew last week and that a team from Newport News Shipbuilding was working hard on the remaining four. USNI News reported after the last media embark to Ford in November that the seventh was supposed to have been completed by the end of 2020 and that all 11 would be done by April.

Even despite the ship not having all 11 to train with, Lanzilotta said they’re already seeing efficiency and the potential for greater sortie-generation rates “by virtue of the design improvements inherent in the Advanced Weapons Elevator design – so if you saw it up on the flight deck, we’ve now got a different layout of the weapons elevator doors. So the doors themselves come up off the flight deck and open like a clamshell. It’s not a giant wind-blast-catcher like on the older ships that would stop movement around the flight deck. So that in and of itself, the upper stage elevators opening on a lower profile so we can get weapons from the weapons transfer and assembly areas to the flight deck, that in and of itself will improve flow and improve the quickness that we have in terms of re-arming aircraft when we’re in battle. But in order to do that, we’ve got to get the whole air wing onboard, we’ve got to fill the magazines with weapons, even if they’re practice weapons, and we’ve got to do it. So that’s the stuff that I look forward to doing in the coming years.”

Several officers in charge of various aspects of flight deck operations noted that the carrier qualifications they’re doing now with new pilots is very different than cyclic operations they’d do with an air wing onboard: usually an air wing would want to launch all its planes as quickly as possible, aiming for that high sortie-generation rate, and then the planes would come back hours later after their mission and all land on the carrier in rapid succession. With carrier qualifications, pilots launch off the ship and then circle around and land again quickly, getting in several repetitions before handing the jet over to another new pilot.

“Right now the things that we’re doing are much more tactical (than focusing on sortie-generation rates from a programmatic perspectic): we’re qualifying aviators that are flying on and off the ship, and by doing that we’re finding what our throughput is, how can we find ways to do things more efficiently. I’m sure you noticed on the flight deck: that is a giant flight deck, so there are ways that, once we embark the entire air wing – back in November during our Independent Steaming Event Number 13 we embarked a portion of Air Wing 8 – when we embark a larger portion of that air wing and then the whole air wing, we are going to find, I think, great efficiencies in the flight deck size and layout. So we’re still building on that,” Lanzilotta said.

“What I do see is a lot of opportunity for innovation.”

A view of the flight deck on USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) from the tower of the ship on March 9, 2021. USNI News photo.

Cmdr. John Peterson, the Air Boss on Ford, said the layout of the flight deck brings great potential for efficiency. Ford’s island is farther back than the island on a Nimitz-class carrier; on a Nimitz CVN, some aircraft would be parked behind the island to make use of that space. However, to tow those aircraft into position to be launched, or tow them forward on the flight deck to be rearmed or refueled, they’d have to cross into the area where planes would be landing – meaning that, if jets are landing, any aircraft parked behind the island has to stay behind the island until aircraft recovery ends.

“By moving the tower aft, it allows us to put more aircraft out front, and that means we can move them around and we don’t have to stop landing aircraft in order to be able to generate sorties, to move people up, to send them up to the catapult. So that’s a huge advantage that we have on this boat that will make it more efficient so we can generate more sorties,” Peterson told USNI News during a tour of the ship’s tower.

He praised the EMALS and the new Advanced Arresting Gear (AAG) systems for being able to tailor the force used to launch or recover a plane to the size of the plane, meaning it puts less stress on the airframe and also on the ship.

“If you’re walking around a Nimitz-class carrier and we are slinging airplanes downrange, then every time that catapult goes to the end, you feel the whole boat shake and vibrate. It doesn’t happen on this boat. Because of the electromagnetic catapult, as it goes down, [EMALS] has a deceleration at the end, and you are able to launch those without that huge vibration coming across. It cuts down on the noise, all those types of things,” Peterson said, noting this is better for the aircraft, the pilots inside and the ship.

Similarly, AAG can unwind more or less of the arresting wire when a landing aircraft catches it with its tailhook based on the weight of the plane, creating a gentler stop for the planes.

On the Nimitz class, “it’s just an immediate pull as soon as you hit the wire. This is a little bit slower, again, to kind of go out, so that helps you out with the wear and tear. So not only is it better for our equipment, but it’s better for the airplanes that we’re trying to make last for 30, 40 years, where we’re not just ripping those hooks and everything else out there. Huge improvement for the capability of the team.”

Peterson praised the EMALS and AAG operators and maintainers for getting better and better with the new systems each time the ship goes out to sea, adding that they’ve started to recognize small maintenance issues and correct them before they turn into bigger failures, creating greater system readiness as they refine their preventative maintenance practices over time.

The flight deck crew of USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) launches and recovers F/A-18E-F Super Hornets from Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 122 as pilots in the West Coast fleet replacement squadron conduct carrier qualifications on March 9, 2021. USNI News photo.

Lt. Christopher Jones, the flight deck officer, told USNI News that he too had seen improvement over time from his perch in Flight Control.

“As we get new folks in, get them trained up – shooters, the catapult launch officers – once we get that team working together and we start gelling as a unit, obviously operations start to go faster, we start to get more sorties in. Obviously working with the new equipment, the maintainers have gotten 100-times better at maintaining the gear and actually speeding up processes to repair gear, so we are able to launch aircraft a great deal faster than we could a year ago,” he said.

One of those operators – Aviation Boatswain’s Mate (Launching and Recovery) 1st Class Fiona McMahon, a bubble operator and the maintenance support leading petty officer – told USNI News that part of the ability to operate EMALS faster comes from cutting out the middle man during certain tasks. For example, she said, on Nimitz-class carriers – she served on USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) and USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) – the shooter will set a capacity selector valve (CSV) setting to control the steam pressure to the catapults, and a panel operator below deck has to ensure their setting is the same, “and it’s like a middle man is in between relaying this information; but with EMALS, we cut out the panel operator.”

Overall, she said, “I feel as though EMALS is a lot faster as far as setting up the [catapult] and getting the aircraft off deck without the multiple stations to ask, are we clear to maneuver, are we clear to launch; it’s just less personnel to speak to, so it’s a quicker, faster response in order to get the aircraft off deck.”

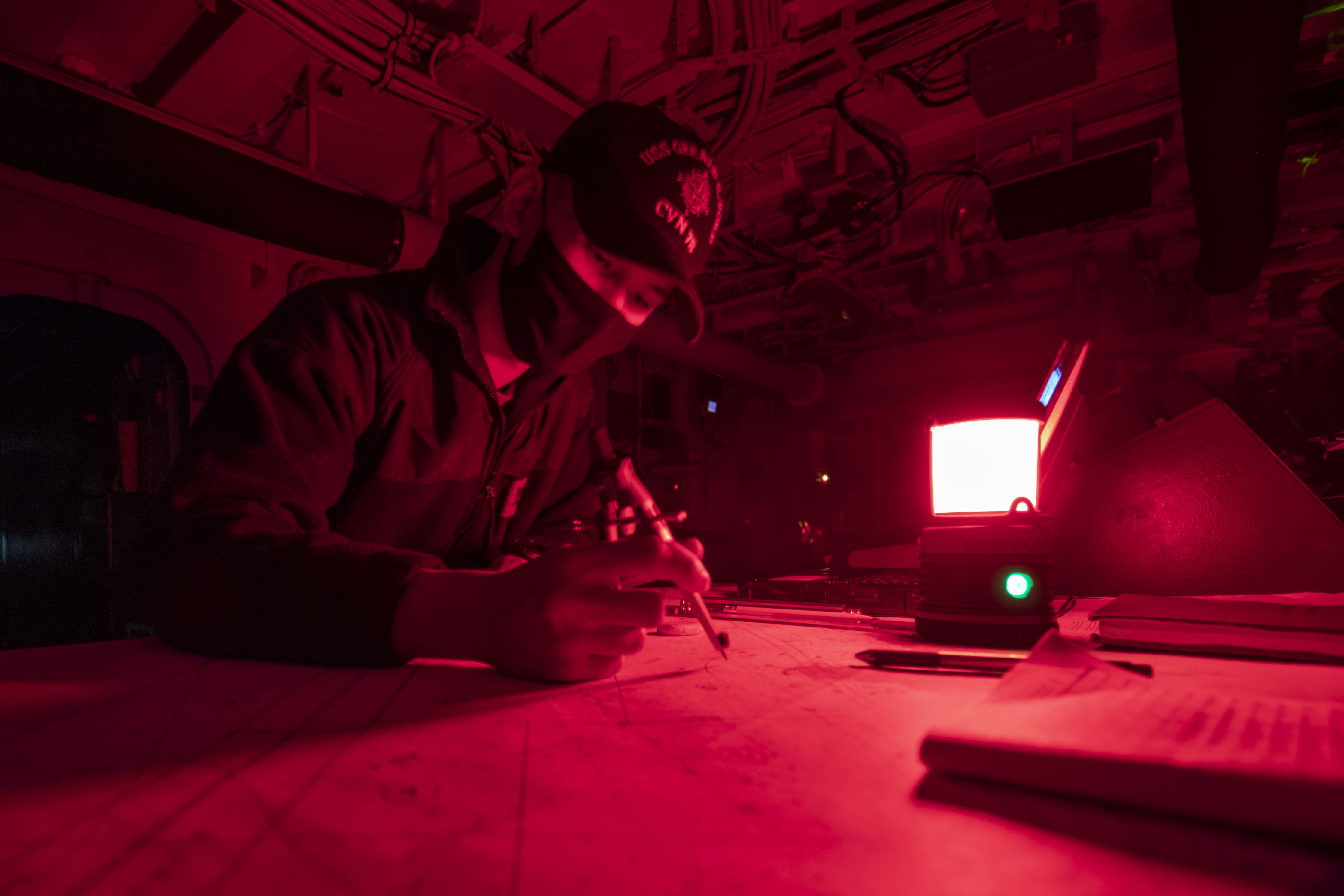

Quartermaster 3rd Class Carl John Caidic, from Oak Harbor, Washington, assigned to USS Gerald R. Ford’s (CVN 78) navigation department, plots a point on a paper chart in Ford’s pilot house, Jan. 31, 2021. US Navy photo.

Lanzilotta, speaking to USNI News later in the trip from the hangar bay, pointed to additional design changes elsewhere on the Ford class that lead to more efficiency and fewer man hours for maintenance compared to the Nimitz class.

Some are as simple as reducing the number of moving parts: whereas the Nimitz carriers have two sets of divisional doors that can split the hangar bay area into three separate hangars, Ford only has one. Lanzilotta said they don’t really need three distinct spaces, and the new design is one less thing to maintain.

Additionally, he pointed to fire watch practices as another way to reduce workload. On the Nimitz class, “if you have aircraft with fuel in them in the hangar bay, you have to man these conflagration stations. You see them in the overhead. This ship doesn’t have those; it has one consolidated conflagration station, or basically a fire watch, and it’s enabled by all the cameras you see around the hangar bay. So one person sits in an office in the middle, and they’re backed up by a secondary if we need it, and they get to basically monitor the entirety of the hangar bay with high definition color video.”

“It’s one of those efficiencies we’ve found, and I love it,” he said.

Additionally, the Ford class has storage elevators like the San Antonio-class amphibious transport docks instead of the vertical package conveyors that Nimitz carriers do. Replenishments at sea on a Nimitz carrier turn into a whole production, with hundreds of sailors breaking down pallets of fruit, cereal, kitchen staples and more and putting them onto the conveyor for sailors in lower decks to repackage them again in chilled or dry storage rooms.

With the elevators, Lanzilotta said, the goods can stay on the same pallet the entire time, “so we don’t have a 200-man working party that’s de-palletizing, feeding to a vertical package conveyor – which by the way those VPCs are very maintenance-intensive to keep working on the Nimitz-class – and we don’t have them anymore.” The elevators on Ford are like the LPD he formerly commanded, he said, and “they’re the old-school kind of elevators with wire and rope. … They carry a lot more than you can with a VPC, and you don’t have to de-palletize and re-palletize the stuff.”

Remaining Workload

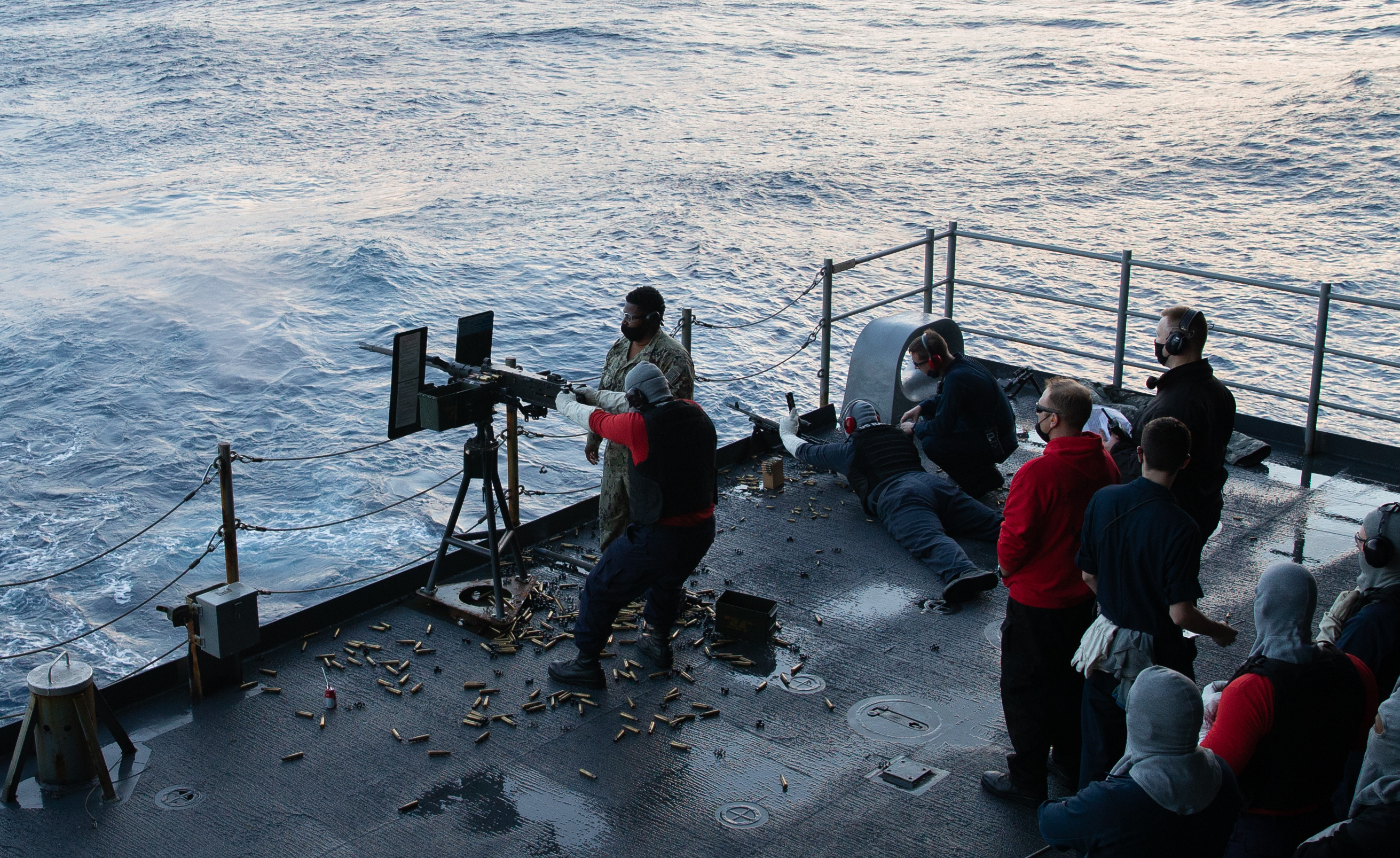

Sailors assigned to USS Gerald R. Ford’s (CVN 78) weapons department conduct a live fire weapons qualification exercise. Ford is underway conducting an independent steaming event on Jan. 28, 2021. US Navy photo.

Ford is at sea now and, after another in-port working period, will go to sea once more before the post-delivery test and trials (PDT&T) period ends. At that point, the crew will be solely focused on getting ready for full-ship shock trials and will no longer be available to help meet fleet training requirements.

For now, though, the ship is balancing its own testing and maintenance needs with that of the fleet.

The ship is in the third of five phases of CSSQT, Chief Warrant Officer 3 Todd Williamson, the ship’s fire control officer, said during a tour of the ship. The first phase focused on ensuring sailors could properly maintain the self-defense sensors, weapons and combat systems, and a second in-port training phase allowed operators to train against synthetic targets in the computer system so they could learn the basics of tactical operations. Some of the carrier’s systems are the same as in other ships in the fleet – Fire Controlman 2nd Class Sam Lantinga said things like the Close-In Weapon System work the same – but the Ship Self-Defense System and the Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile are a bit different due to Ford having a unique radar for the combat system to interface with, he added.

Williamson said Ford is in the third phase now, which is at-sea training. The combat system has been tracking live targets such as Leer jets and high-speed maneuverable targets, using sensors and weapons to track them as they move near the carrier at sea.

“What we’re doing right now is a whole lot of dry runs so that we know that it’s safe to fire live missiles at towed targets and fast targets and surface targets and stuff like that,” Lanzilotta explained while discussing the ongoing CSSQT activities.

Next, Williamson said, the ship will go through a risk-reduction period in port, where the operators will look at the script of the live-fire missile shot events. Then, when the ship is next at sea, comes the live-fire event itself. Williamson said that, unlike a live-fire event during pre-deployment training, this isn’t meant to test the operators’ knowledge; rather, it’s meant to make sure the systems are all installed correctly and that the crew can safely operate and maintain them.

The next at-sea period for the carrier will also bring another round of carrier strike group operations.

The last time Ford did this, there wasn’t a cruiser available to operate with the CSG, so the air warfare commander that would typically operate from a space on the cruiser worked from aboard Ford.

Lanzilotta said there’s still a lot to be learned about how Ford can support different CSG functions from the carrier itself, by communicating with other Navy ships performing those functions, and by communicating with allied and partner navy ships performing those functions.

“This ship’s air defense suite is a lot different than what the SPY radar brings in a guided-missile cruiser. … We’re going to do more of that here in three or four weeks. There’s no doubt in my mind that whenever we do air defense exercises as a Navy … we always come back with lessons. Like, hey, we need to talk on this kind of a voice net, not this other kind. Is [satellite communication] best for this, or is line-of-sight best for this? And the ship can do all of the above, which is really cool, and I think what we want to do here first is verify, can we do all the things you need to do as a flagship as an aircraft carrier, and then branch into … what can we do differently, how do we take it to the next level?” the skipper said.

A shock blast is detonated off the starboard side of USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71), September 19, 1987. The test was conducted to demonstrate the carrier’s ability to withstand underwater shock waves. US Navy photo.

Even as PDT&T winds down, Lanzilotta said he and the crew are already thinking about shock trials.

“As you’ve been walking around the ship, if you have a keen eye and you’ve been on lots of carriers, you’ll see some extra wires and things like that. All of those connect to sensors and data acquisition systems that we’re going to use in order to measure the ship’s performance during” full-ship shock trials, he said.

“We’re going to remove some of the fragile items on the ship – so this room is a perfect example, I am not going to have this room in this configuration for the shock trial,” he said while speaking from the CO’s in-port cabin.

“A lot of the things in this room are family heirlooms from the Ford Foundation, so they’ll have to be protected. Similarly, there are things on the ship that we just know are not intended for a battle shock scenario – something like a commercially bought printer that you connect to your computer – those printers aren’t meant to withstand ship shock trials, so we’re going to remove them from the ship and save the taxpayer the expense that we already know we’re likely to get. That’s quite a bit of work when you have a ship with 5,000 spaces in it, so we have to prepare all of our gear. We’re also going to prepare the crew: so the crew has to know what to expect, they need to practice their damage control procedures because that’s something that we all need to be good at, and when we shock the ship we need to make sure that we have the ship in as ready a condition as we can.”

Despite the ship’s heavy workload, the crew can’t prioritize just their own tasks. On the East Coast today, two carriers are tied up in mid-life refueling activities, two are in maintenance and one is deployed, leaving just Ford to support the needs of new pilots and new carrier sailors who need to practice their skills at sea. Lanzilotta said sailors are working on his ship wearing ball caps from USS George H.W. Bush (CVN-77), USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75), USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74) and even in-construction John F. Kennedy (CVN-79), all trying to get some practice applying the skills they learned in the schoolhouse while operating on a ship at sea.

Similarly, new pilots from West Coast fleet replacement squadron Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 122 were flying on and off the deck as they learn to fly the F/A-18E-F Super Hornet.

Tackling Maintenance

Aviation Boatswain’s Mate (Fuels) 3rd Class Jacob Clauss, left, from Parrdeeville, Wisconsin, assigned to USS Gerald R. Ford’s (CVN 78) air department, explains the fuel purification process to Capt. Paul Lanzilotta, Ford’s prospective commanding officer, in Ford’s pump room 5, Feb. 1, 2021. US Navy photo.

A key part of PDT&T for Ford was catching up on construction and maintenance work that hadn’t been completed yet, and getting ahead of some of the maintenance and modernization work that lies ahead in a yard availability following shock trials.

In the case of the Advanced Weapons Elevators, Lanzilotta said the work is 93 percent done, with four still being worked on. Several dozen contractors are on the ship at any given time, even during operations at sea, to get the elevators done and turned over to the crew as soon as possible.

He said he and a leadership team look at maintenance every day and what can be done now versus what has to wait for an in-port period or the final yard availability at the end of this year. Some activities aren’t hard but just take a long time – opening and inspecting every single electrical switchgear panel on the ship – and the more the crew can do now, the less there is to worry about in the shipyard when more extensive work will be happening, he said.

Cmdr. Homer Hensy, the chief engineer on Ford, said the carrier was originally looking at a nine- to 11-month planned incremental availability after shock trials, but “we identified there was risk at that timeline on there, and we started moving items to the left. So there’s been a tremendous amount of maintenance that we would have done during the planned incremental availability that has been done during” in-port and at-sea periods throughout 2020 and 2021.

He said doing lower-risk work like installing software updates, as well as critical path items that can take a long time such as installing the four Mk 38 machine gun systems, today can reduce risk to the schedule later on.

Hensy couldn’t say exactly how much work had been pulled up from the PIA and done early, and therefore how that affected how long the PIA might take.

“We’re definitely trying to get back out – I believe the target that we’re shooting for, we will be back in the fight next year,” he said